Heritage behind the royal family of porcelain

Fascinating exhibitions provide a glimpse into the sources of some of China's most celebrated pottery

In 1369, a porcelain kiln was built in Jingdezhen, in Jiangxi province, to serve the imperial courts of the newly established Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) - and thus began the city's story as a porcelain hub.

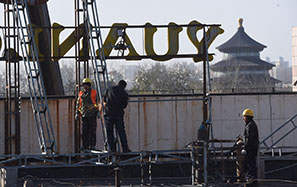

At Beijing's Palace Museum - also called the Forbidden City, the country's royal palace from 1420 until the end of Chinese monarchy in 1911 - two exhibitions have opened showcasing part of the history of imperial ceramics.

Whether in pieces or as complete items, the charm of these artifacts is unmistakable.

|

Visitors look at the ongoing exhibitions that showcase ceramics made in China's porcelain hub, Jingdezhen, for imperial courts during the Ming and Qing dynasties at the Palace Museum in Beijing. The imperial-kiln ceramics represent a zenith in the country's porcelain-making history. Photos by Jiang Dong / China Daily |

The Ming Imperial Porcelain: A Comparative Exhibition of Archaeological Findings at the Imperial Kiln Site in Jingdezhen and Chenghua Period Porcelain in the Collection of the Palace Museum, comprises 183 sets of porcelain from the reign of Chenghua (1465-87).

Seventy-six exhibits are from the Palace Museum collection, while the rest are pieces with defects found by archaeologists in kilns in Jingdezhen, according to Lyu Chenglong, head of the Porcelain Research Institute at the Palace Museum.

"Only the best pieces were sent to Beijing. Those with defects were broken and buried at Jingdezhen. You can immediately tell the difference in this exhibition," says Lyu.

"The copying of such pieces by the public was strictly prohibited. So you do not see similar pieces elsewhere."

Speaking about the pieces with defects, Lyu says failure to get the color or shape right were common reasons for the pieces to be destroyed. Some were rejected for other "small" reasons.

"For instance, we found broken items in Jingdezhen, some as exquisite as those housed in the Forbidden City, but with mistakes in the chronological information, or with an extra paw for the dragons."

In 2015, the Palace Museum held a similar event on imperial kiln items from the 1368-1435 period, covering three emperors, but Lyu says the Chenghua period needed to be emphasized because he believes it represents a zenith in porcelain making during the Ming Dynasty.

"Chenghua imperial porcelain is among the most delicate, and the surfaces look like they are polished using oil," says Lyu. "Their patterns and colors are not flamboyant, but they reflect harmony and elegance.

"Emperor Chenghua may not have been a good ruler - nurturing notorious officials - but we cannot deny he had taste."

Lyu also points to the overseas artistic influences seen in the imperial kiln ceramics of the Chenghua era, reflecting cross-cultural communication. Some exhibits from the time show typical Islamic patterns from western Asia.

"Chenghua porcelain is an incredible treasure due to its large variety and shapes," says Geng Baochang, 94, one of the country's most renowned porcelain researchers, after visiting the exhibition. "But it was once thought there were not many items surviving from that period.

"So, when the Chenghua works are brought together, it is really a brilliant feast, not only for researchers but also for the public."

Meanwhile, another exhibition, Porcelain from the Ming and Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) Imperial Kilns: Archaeological Finds at the Palace Museum and in Jingdezhen, showcases a total of 163 sets from both places that have been unearthed since 2014, giving visitors a view of how the kilns were managed and how the porcelain was made.

"Some of the finds have filled gaps in academic research," says Lyu. "Many patterns that are not seen in items that have survived were found during the excavations."

Examples of how researchers have been helped are finds relating to the period 1436-64.

The earlier collections did not have any items that could be traced to this period, and this led some to speculate that the kilns had halted operations during that time.

But the discovery of an earth layer from that period at Jingdezhen, which contained a large number of porcelain shards, debunked that theory.

In 2014, a site containing broken porcelain was also discovered at the Forbidden City, which could have been the dumping ground for used porcelain from the imperial court.

According to Wang Yamin, deputy director of the Palace Museum, the two exhibitions are a part of an agreement on academic research signed in 2014 between the museum and the Jingdezhen Archaeological Research Institute.

"A vast majority of the 360,000 porcelain items at the Palace Museum come from Jingdezhen," says Wang. "The two places are closely connected. It is part of an inevitable trend of letting academic research serve the public. More comparative exhibitions showcasing imperial porcelain from other reigns of the Ming Dynasty are in the pipeline," he says.