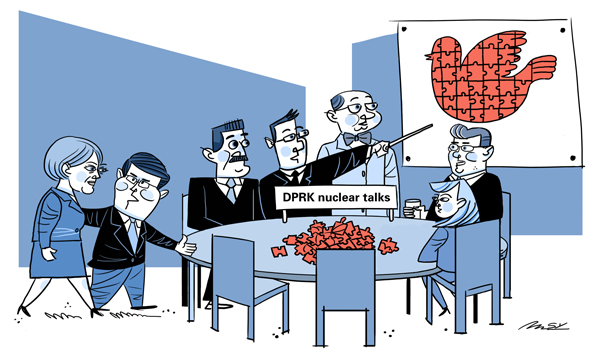

Could Iran deal be model for DPRK?

The international community has been struggling to respond to the Democratic People's Republic of Korea's steadily expanding nuclear program. US President Donald Trump has oscillated between massive threats to devastate the DPRK and holding out the prospect of talks.

On Monday, the UN Security Council unanimously adopted a resolution to impose fresh sanctions on the DPRK for violating the previous Security Council resolutions by conducting its sixth and strongest nuclear test on Sept 3. Last week, Federica Mogherin, the European Union's foreign policy chief, said Brussels would be prepared to take additional measures against Pyongyang, including travel bans and asset freezes on senior DPRK officials.

Why does the DRRK issue matter to Europe? Simply because any conflict in Northeast Asia could have huge geopolitical consequences and an immediate impact on global supply chains.

Now German Chancellor Angela Merkel has said the Iran deal could be a possible model to resolve the DPRK issue. The Iran model refers to the EU-led negotiations to curb Iran's nuclear program in return for the gradual lifting of sanctions.

The negotiations were initially dismissed by the United States but when it realized there was no other game in town, it came on board. The talks were tough and involved all five members of the UN Security Council plus Germany. And the International Atomic Energy Agency was brought in to monitor and supervise the agreement.

So far the deal has worked well, although there are voices in the Trump administration calling for it to be abandoned. The EU and China have made clear this would be a huge mistake.

There are of course significant differences between Iran and the DPRK. Iran was never as isolated from the international community. Even though the US broke off diplomatic relations with Iran after the 1980 hostage crisis, there were always some channels of communication. Sanctions, too, were never watertight with much illicit trade conducted through the Persian Gulf. Many Iranian companies had branches in Dubai to make and receive payments. Furthermore, Iran has a large market and huge oil and gas resources that were tempting for Western and Chinese companies.

The EU is also a more plausible leader of negotiations than the US or China, for completely different reasons, though. It has a policy of "critical engagement" with the DPRK which combines pressure with sanctions and keeping communication and dialogue channels open. Unlike the US, the EU is not regarded as a threat by the DPRK and does not share a border with it like China. And seven EU member states have diplomatic missions in the DPRK.

It does of course take two to tango and so far there is little sign of the DPRK willing to take to the dance floor. The US and the EU have had various "unofficial "meetings with senior DPRK officials in recent years but no positive signals have emerged from the DPRK. The argument that Pyongyang's nuclear weapons program diverted resources from the necessary investments in social and economic development projects, which would have benefited the DPRK population at large, fell on deaf ears. In response, Pyongyang always refers to the overthrowing of Saddam Hussein and Muammar Gadhafi in Iraq and Libya, respectively, to highlight the US' real intentions of intervening in other countries' affairs.

Which means the security of the government is clearly the number one priority for Pyongyang. So Pyongyang might be willing to come to the negotiating table only after it is convinced that it has credible deterrent against attacks.

No one can say when this moment will come. But to make it possible sooner rather than later, Beijing and Brussels have to maintain pressure on Pyongyang, as well as ensure Washington does not walk away from the Iran deal, as that would send a wrong signal to the DPRK.

The EU's commitment to dialogue and a peaceful outcome is a reflection of Churchill's famous saying, "to jaw-jaw is better than to war-war".

The author is director of the EU-Asia Centre in Brussels.