The face behind a drummer's beat

|

|

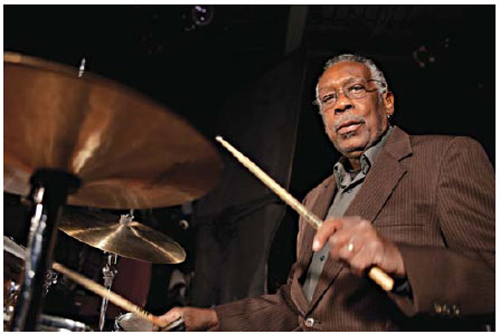

Clyde Stubblefield, unpaid for work that others used. Benjamin Franzen |

No matter who you are, you probably know Clyde Stubblefield's drumming.

If you've heard Public Enemy's "Bring the Noise" or "Fight the Power," you know it. If you've heard LL Cool J's "Mama Said Knock You Out," or any number of songs by Prince, the Beastie Boys, N.W.A., Run-D.M.C., Sinead O'Connor or even Kenny G., you definitely know it, even though Mr. Stubblefield wasn't in the studio for the recording of any of them.

That is because he was the featured player on "Funky Drummer," a 1970 single by James Brown. The 20-second drum solo has become, by most counts, the most sampled of all beats. It has become part of hip-hop's DNA.

Yet the early rappers almost never gave credit or paid for the sample, and if they did, acknowledgment (and any royalties) went to Brown, the songwriter.

"All my life I've been wondering about my money," Mr. Stubblefield, now 67 and still drumming, says with a chuckle.

A new project tries to capture at least some royalties for him. Mr. Stubblefield was interviewed for "Copyright Criminals," a documentary by Benjamin Franzen and Kembrew McLeod about music copyright law, and for a special "Funky Drummer Edition" DVD of the film, Mr. Stubblefield recorded a set of ready-to-sample beats. Anyone willing to pay royalties of 15 percent on any commercial sales - and give credit - can borrow the sound of an architect of modern percussion.

"There have been faster, and there have been stronger, but Clyde Stubblefield has a marksman's left hand unlike any drummer in the 20th century," said Ahmir Thompson, also known as Questlove of the Roots. "It is he who defined funk music."

Born in Chattanooga, Tennessee, Mr. Stubblefield was f irst inspired by the industrial rhythms of factories and trains. One day in 1965 Brown saw him at a club in Macon, Georgia, and hired him by in 1965. Through 1971 Mr. Stubblefield was one of Brown's principal drummers, and on songs like "Cold Sweat" and "Mother Popcorn" he perfected a light-touch style filled with the syncopations sometimes called ghost notes.

"His softest notes defined a generation," Mr. Thompson added.

"We just played what we wanted to play on a song," Mr. Stubblefield said. "Nobody directs me."

For 40 years he has lived in Madison, Wisconsin, where he plays playing gigs there with his own groupand playing on the public radio show "Michael Feldman's Whad'Ya Know?"

The technology of sampling - isolating a musical snippet from one recording and reusing it for another - kept Mr. Stubblefield from greater recognition. "Funky Drummer" didn't appear on an album until 1986, when it was on "In the Jungle Groove," a Brown collection that was heavily picked over by the new generation of sampler-producers.

The lack of recognition has bothered Mr. Stubblefield more than the lack of royalties, he said, although that stings too. "People use my drum patterns on a lot of these songs," he said. "They never gave me credit, never paid me. It didn't bug me or disturb me, but I think it's disrespectful not to pay people for what they use."

The "Funky Drummer Edition" of "Copyright Criminals" includes Mr. Stubblefield's beats both on vinyl and as electronic files, and in addition to any licensing, he also gets a small royalty from the DVD, said Kembrew McLeod, one of the filmmakers.

Albums with ready-made beats are nothing new in hip-hop. By his reckoning, Mr. Stubblefield has done four or five, but not all of those have paid him his royalties either. "They sent us royalty papers, but no checks," he said of one such album made for a Japanese company.

Lack of credit was also an issue with many musicians who played with Brown. The lack of recognition has bothered Mr. Stubblefield, who suffers from end-stage renal disease, more than the lack of royalties, he said, although that stings too.

"People use my drum patterns on a lot of these songs," he said.

"They never gave me credit, never paid me. It didn't bug me or disturb me, but I think it's disrespectful not to pay people for what they use."