China's shaping up to be obesogenic

Updated: 2011-09-21 10:23

By Erik Nilsson and Liu Zhihua (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

|

Many weight-loss centers in cities like Beijing and Shanghai are helping youngsters win the battle of the bulge. Provided to China Daily |

Weight-loss camps are sprouting in many cities to deal with growing obesity among children, amid rising affluence. Erik Nilsson and Liu Zhihua report.

Wang Di's classmates couldn't recognize her this semester. The 16-year-old weighed 129 kg before summer and fewer than 100 kg after.

"They thought I was someone else," Wang says. "They couldn't believe their eyes."

She burned the first 21 kg in her first 42 days at Body Sport weight-loss camp, which has been attended by more than 1,000 people from across the country since it opened in 2008.

Most major Chinese cities now host such centers, and a growing number of their customers are young, as childhood obesity increases.

"I knew I was fat and desperately wanted to be beautiful," Wang says. "Now, I am."

Because the girl from Shanxi province's Yuncheng city was determined to slim, she searched online until she found the weight-loss program in Beijing, where she spent 84 intensive days starting in May.

She also hired a personal trainer for 150 yuan ($23.50) an hour.

"It was exhausting and sometimes very boring but worth the effort and money," she says.

"I was going to do whatever it took."

Trainer Chen Shoujun says that, like Wang, 90 percent of the children decide themselves to go to Body Sport. About 60 percent are girls. And 60 percent go because they are concerned about appearance rather than health.

"Most obese children feel peer pressure," he says.

Parents pay an average of 10,000 yuan ($1,566) for six weeks' training, Chen says.

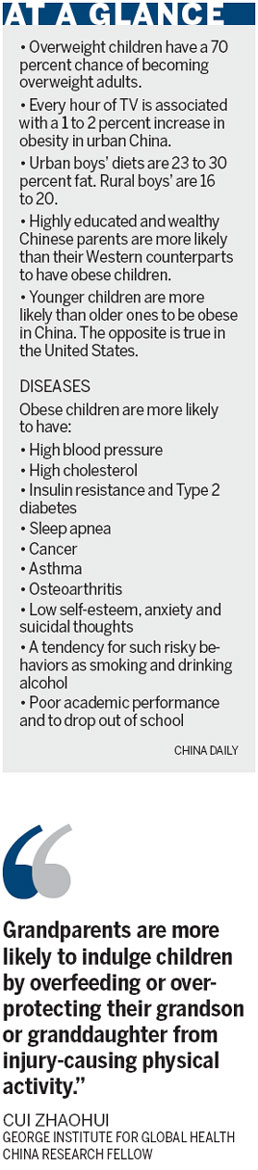

George Institute for Global Health China research fellow Cui Zhaohui believes the proliferation of weight-loss camps for children coincides with the country's growing prosperity.

"The increase in obesity is a price developing countries must pay for modernization," the doctor says.

"The rise of obesity is inevitable considering the current (lack of) knowledge about its prevention and the necessities of modernization. But the rise of childhood obesity can be minimized."

Childhood obesity has more than tripled in China over the past 30 years, according to a survey conducted by Chinese Association of Students Nutrition and Health in 2009.

Currently, an estimated 42 million Chinese children are obese.

The designations of "overweight" and "obese" are determined by Body Mass Index - which is calculated by dividing a person's weight in kilograms by the square of one's height in meters. Results from 25 to 29.9 are categorized as overweight, while anything more than 30 is obese.

"Modernization, globalization and urbanization are changing the environment we live in to become more 'obesogenic', leading to people either eating more or becoming less active," Cui says.

While many of the culprits fit the same lineup as other countries', several are China specific, he says.

One is a history of starvation and malnutrition, Cui explains.

"With these experiences, Chinese people have come to hold the belief that obesity is a sign of prosperity, happiness and health," Cui says.

Another is the fawning that comes with the country's family planning policy.

"The child's parents and grandparents pamper their only child by overfeeding the 'little emperor'," Cui says. "Furthermore, food that used to be distributed among his siblings is now devoured by just one person."

Grandparents' role in child rearing, coupled with a traditional preference for boys, also contributes.

"Grandparents are more likely to indulge children by overfeeding or overprotecting their grandson or granddaughter from injury-causing physical activity," Cui says.

They are especially likely to overfeed the favored boys, Cui says.

And Chinese society emphasizes academic performance more compared with the West.

"Relatively less attention has been paid to the establishment of healthy lifestyles, including healthy diets and physical activity (in China)," Cui says. "The extra time spent on academic tasks partly deprives children of activity."

Wang says she believes she spent too much time hitting the books and not enough time being active.

She says she has been sticking to her trainer's advice - to eat well, skip snacks and take walks between classes. But this has gotten trickier as she has become buried in homework.

Disparities exist between the country's rural and urban youth, Cui explains.

In 2006, 10 million of China's obese children lived in urban areas, while 23 million dwelled in rural areas.

Estimates put the 2011 figures at 13 million in cities and 29 million in the countryside, Cui says.

"Greater attention should be paid to children, especially boys, in rural areas," Cui says.

"That is, considering their increasing tendency to be overweight and obese, the large population, the future costs of obesity-related chronic diseases, and the cost and limited health resources in these areas."

Cui believes city sprawl is, ironically, magnifying the threat to rural dwellers.

"In rural areas, increasing urbanization makes children lose their playgrounds and their vegetable gardens to work in, and exposes them to high energy-density foods and motorized transport."

In addition, China's sports facilities are fewer than the global per capita average, Cui says.

But while many factors are country specific, some are imported.

"The dietary pattern in Chinese children is rapidly shifting to a Western diet," Cui says.

George Washington University Medical Center researcher Tsung O Cheng writes in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, "Because of the efficient advertisements of such fast food giants in the United States as McDonald's and KFC, Chinese children are devouring American fast food faster than ever."

Studies show children younger than 8 can't decipher advertisements' intentions and accept them as "accurate and unbiased", Cui says. A 30-second commercial can influence brand preferences in children as young as 2.

Cui points out the percentage of Chinese children whose dietary fat intake exceeds the World Health Organization's recommended maximum of 30 percent increased from 20 to 50 percent over the past two decades.

Zhen Kaiyuan has been avoiding fast food since camp.

"Body Sport's food isn't delicious, but it works for losing weight," the 10-year-old says.

The servings are low in fat and salt. There is no pork or snacks, Chen says.

Zhen, a native of Guangdong's provincial capital Guangzhou, went from 74 to 61 kg in 42 days.

"I cringed when mom told me I was going to a summer camp in Beijing to lose weight," Zhen says.

"But it turned out to be fun. And it worked, although it was hard."

Trainees do two hours' anaerobic exercise and another two of aerobic exercise a day.

"Many classmates had told me I was too fat," Zhen says.

"Their intentions were kind-hearted. But it felt bad to be different from others."

His mother, Liang Shufen, believes it was worth it.

"He's in his best shape since he was born," she says.

Zhen and Wang both enjoyed stationary bicycling.

"I sweated a lot," Zhen says.

"I worked hardest the first week. After that, it started to get repetitive."

Liang says she could tell Zhen wasn't working as hard later in the camp, because his clothes weren't soaked with perspiration.

"But the training still helped him lose so much weight," she says.

"He was happy. It was a special experience."