From absurdity to reality

Updated: 2012-01-12 14:39

By Chitralekha Basu and Song Wenwei (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

|

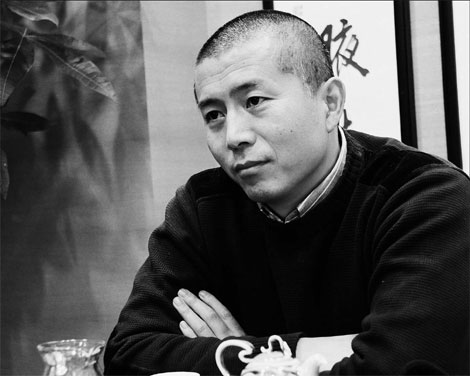

Author Bi Feiyu, who has spent the past year traveling around half the world, says he is now longing to get back to a life of quiet contemplation. Song Wenwei / China Daily |

Author Bi Feiyu says his storytelling has now moved from the fantastical to the literal. Chitralekha Basu and Song Wenwei report.

My colleagues and I have been pursuing Bi Feiyu for months. Of all the major writers in China we managed to pin down and interview, Bi proved to be the most elusive. It wasn't as if he was playing hard-to-get. Since winning the Man Asian Literary Prize (MALP) for Three Sisters in March 2011, Bi - whose first name, Feiyu, means "one who flies across the universe" - has quite literally been living up to his name. He has been attending literary dos, conferences and book signings around the world. "I haven't slept in the same bed for three consecutive nights," he says. But even before the big MALP win, events featuring him at literary festivals in Beijing would sell out the fastest.

The man who has been billed by media and marketing professionals as "China's finest male writer with the deepest understanding of the female psyche" - much to his consternation, in fact, but we'll come to that later - was also, by popular (read, female) consensus, one of the nation's dishiest novelists.

The 47-year-old, whose shaven head shows off his prominent cheekbones and brooding, vulnerable eyes to his best advantage, has the draw of a movie star.

When we reach the residential compound in which Bi lives in Jiangsu's provincial capital Nanjing, the staff member manning the gates tells us, assuredly, "Oh, he only needs to win the Nobel now. The rest are already in his kitty."

Bi won the Lu Xun Award - twice. He also took the Mao Dun Prize, the highest national literary award, last September. He was the youngest among fellow heavyweights, such as Zhang Wei and Mo Yan, to do so. He was also long-listed for The Independent Foreign Fiction Prize in 2008 for The Moon Opera.

Bi joins us soon, leading the way through a maze of corridors, restaurant kitchens, private enterprises' back offices, a shopping mall escalator and across a noisy highway with heavy traffic. He kneels down, on the way, to pet a golden retriever that clamors for his attention at a magazine kiosk. ("I have a female of the same breed, and he can smell her on me," he says, tenderly).

Finally, after what feels like a journey across the author's personal world, we are led into the picture-perfect precincts of a traditional teahouse, where Bi talks to us.

The idea for Massage, which won the prestigious Mao Dun Award, came to him in a moment of epiphany, he says.

For years, Bi had been going to a massage parlor staffed by blind masseurs late in the evening.

One night, after packing up, as both clients and staffers were getting ready to go home, the lights were switched off. A woman masseuse took Bi's hand and led him through the pitch-dark corridor.

"You see, Teacher Bi," she told him, "I can see better than you do."

(Bi had been training special education teachers for the blind for a while.)

The dichotomy between physical blindness and one's sense of vision and perception has served literature well in the past. Celebrated examples include Blindness by Jose Saramago and The Blind Assassin by Margaret Atwood.

The idea that limited vision might actually be an attribute - a gift, offering insight into things that people with normal eyesight may not be able to perceive - had an obvious appeal to Bi, who says he has "always respected limitations".

Extending the metaphor to the scene of China's race to fast-track developmental success and commercial hegemony, he says, "Unlimited power, unbridled energy, full-on development might throw things out of control. I think a little restraint can do good for this country."

But blindness, in Massage, which can be read as a collection of interrelated stories with a blind person at the center of each, Bi says, is more about the actual physical state of being blind and society's response to it, rather than a metaphor.

"I am just trying to bring the things that tend to remain outside the realm of visibility into light," he says.

In the story about Du Hong, for example, a blind girl is urged to overcome her limitations by learning to play the piano and is later applauded for what is, in fact, a lousy performance that is billed as her service to society.

Such tokenism for the physically challenged, Bi says, actually smacks of "condescension and disrespect - the last things the blind would want from you".

Du Hong's public performance is packaged and presented as a payment of her "debt to society".

Nationalistic fervor runs very deep in China, where Olympic medallists are ticked off for omitting to mention the role of society in their makings.

It's precisely the sentiment Bi says he has been trying to satirize.

He obviously does not buy the theory that every performer, athlete and writer ought to be beholden to society and "especially not the blind. Society has done very little for them, so to expect them to have to repay society is total hypocrisy," he says.

Bi, who began his career by writing poems and screenplays for celebrity director Zhang Yimou (Shanghai Triad, for instance), sees his trajectory over the last 10 years as a movement from the absurd to the real.

The bizarre scenario in one of Bi's early stories - The Ancestor, in which the living sleep in coffins and the very ancient great grandmother's teeth are pulled out, one by one, to exorcize the ills plaguing the house - has given way to simple tales, told simply.

Bi says he now prioritizes understanding over imagination.

"In one's 40s, one begins to have a better understanding of things," he says.

"Scientists sharpen their senses of logic and analysis. Writers hone their understanding."

This shift from clever craftsmanship to empathy and intuitive understanding is also evident in the MALP-winning Three Sisters - the story of three women from rural China, trying to make a life at a time of turbulence and general confusion in 1970s and '80s.

"Often, stories set in the 'cultural revolution' (1966-76) years talk about the damage it did to the country's economy and politics," Bi says.

"But the 'cultural revolution' was more serious than politics. I am interested in individuals and how their lives panned out as a result of the social upheaval."

Women - often strong, feisty, ambitious types who do not hesitate to use their sexuality to get what they want - dominate Bi's fiction.

Expectedly, he's a little tired of the "best male writer on women" tag.

"It's a marketing ploy, which probably helps sell a few more copies," he says.

Evidently, the label makes no difference to him, unless, of course, it implies "a disrespect for my ability to write about human nature in general".

But the state of women in China today remains a matter of concern.

"Women are still discriminated against in terms of getting jobs, raising capital for investment, retirement ages, etc," he says.

"If you claim there is equality between men and women in China, you're living in a fairytale."

In his acceptance speech upon receiving the Mao Dun Award in September, Bi said a writer's vocation included the responsibility of leading an exemplary life, beside the obvious task of continuing to write well.

Hectic travel since the Man Asian win in March has continued to distract him from the quiet life of contemplation, inner monologues and focused writing that Bi would rather lead.

Even as the flashbulbs go off and fans crowd around him with questions, comments and autograph requests, Bi is sometimes bothered by the fact that the novel about a doctor's life that he has been trying to write for four years is probably not going anywhere.

"I work best only under conditions of quietness and isolation. Quietude is my oxygen and water," Bi says.

He hopes for a positive turn in March, "when the next unlucky Man Asian Literary Prize winner takes my place".

That's when he plans to stop in his tracks, at least for a while, and turn his gaze inward.