Keeping a healthy mind

|

|

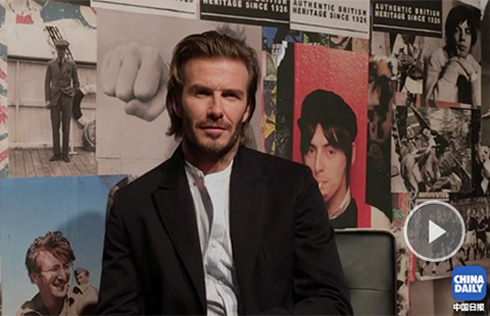

Professor Michael Phillips calls for more efforts to improve the mental health services in the rural areas. [Gao Erqiang/China Daily]?? |

The recent deadly shooting rampage at a US school and a knife attack at a Chinese kindergarten have once again drawn public attention to the issue of mental health.

"These cases sounded an alarm for us. Mental health is not a problem in a single country, but a common issue faced by the world," says Michael Phillips, a mental health professor who has pioneered research on Chinese suicide for more than two decades.

He is also the director of the Suicide Research and Prevention Center of the Shanghai Mental Health Center.

"We need to join efforts globally and work together to deal with mental health issues," he says, referring to the establishment of the Shanghai Mental Health Center-Emory University Collaborative Center for Global Mental Health on Dec 17.

It's the country's first academic cooperative body that focuses on global mental health issues.

The center will work as a platform for domestic and world experts to exchange views and communicate on mental health issues. It will also integrate the country's resources in research and field training, and further improve treatment for patients.

"The center provides opportunities for mutual study, where China and other countries can learn more from each other," he says. "Several developed countries have had their own centers focus on global mental health, but it's very rare in developing countries."

Over the past decades, China has made progress in the field, but there is still much to be done, such as closing the gap between the large demand for mental health care and limited available resources.

Compared with the global average of 4.4, China can only provide around 1.6 hospital beds to every 10,000 people, statistics from the Ministry of Health showed.

According to sources provided by the Shanghai Mental Health Center, mental health problems account for over 20 percent of the total burden of illnesses in China, but the proportion of all health expenditures for mental health is less than 5 percent.

"A major barrier to overcome is how to introduce the resources to rural areas which have so little or no access to mental health services," Phillips says.

He says available services are mainly concentrated in urban-based specialty psychiatric hospitals. There is no financial motivation for doctors to provide high-quality outpatient or community-based care that would reduce admission rates.

"Another barrier is social stigma. The absence of knowledge about mental illness prevents many sufferers from seeking care."

Earlier this year, China's top legislative body adopted the Mental Health Law. The long-awaited national legislation on mental health is expected to help improve patients' access to timely and appropriate treatment.

The law requires general hospitals to set up mental health departments and help train mental health staff in local communities and rural areas.

"The law is a landmark for the development of China's mental health care. It includes many components which have long been under-represented," Phillips says. "Besides, it also has many clauses that will be of considerable interest to people developing mental health laws in other countries."

The collaborative center's first program will start with India, which has accumulated a lot of positive experiences in promoting mental health in local communities.

"India has some similar conditions to China. It has carried out mental health projects among local communities very early, and China could learn from the experiences," he says.