Nam Yohong, the right-hand man to Korea's King Yi Jong, who lived in the first half of the 17th century, had his portrait painted twice by Chinese painters.

The first, in 1627, shows Nam as a benign-looking civil servant with a pair of baggy eyes that may have been the permanent residue of overwork or of the fierce power struggle that jolted the Korean court a few years earlier, in 1623. Yi Jong rose to power by staging a military coup and deposing the king, his much-resented uncle Gwanghaegun. In the portrait, a tense and taut looking Nam appears to be still recovering from the aftershock of the event.

The baggy eyes are still there in the second painting. But the gaunt feel has given way to a look of grim determination - a steely gaze and slight frown that betray an iron shrewdness. This was a man who had seen so much blood flow that eventually such violence would not make him flinch. It was painted in 1647, a year after Nam died aged at age 73.

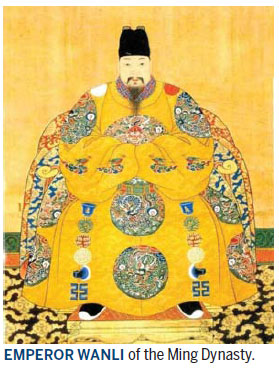

Such emotional subtleties point to the tremendous skill of the portraitists - in Nam's case two. Both were court painters employed by the Chinese emperors to paint the Korean emissary while he was in Beijing. The city was the capital of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) and the succeeding Qing Dynasty (1644-1911).

Fan Jinmin, a history professor at Nanjing University, says the paintings and all other exhibits - about 300 pieces (sets) in total - that have been on view at the Zhejiang Provincial Museum testify to the deep devotion that China and Korea had for one another between the 14th and 17th centuries. In a sense, Nam witnessed the end of that relationship.

"During the time of Ming, Korea was China's vassal state," Fan says. "A Korean king would seek the approval of the Ming emperor if he wanted to banish his queen and marry a new one. When he died he would also be given a posthumous title by the Ming emperor. The influence was not played out merely on the court level. The Chinese lunar calendar, the ultimate time guide for an agricultural society, was widely used in Korea at the time."

Asked if the relationship was formed as a result of China's military and political might, Fan says such factors were certainly crucial. However, he emphasizes the cultural kinships he believes lay at the heart of this prolonged period of mutual respect and admiration.

"Confucianism and classical Chinese culture, the version ordained by the Chinese rulers, made their way into Korea during the Ming era and were enshrined by the ruling elite. Those who wished to enter court service had to take exams that tested their knowledge of Chinese literary and philosophical classics. Of course, they wrote in Chinese."

In the exhibition you can gauge China's cultural influence over Korea from the calligraphic works of Koreans who lived between the 14th and 17th centuries. Many of these are, in fact, works of poetry penned during the process of what Ni Yi calls "literary diplomacy".

Ni is the curator of an exhibition that tries to shed light on the Sino-Korean relationship during the Ming era by constructing a narrative line surrounding Choe Bu, a 15th-century Korean who had the bad luck to encounter strong wind at sea and the good luck to travel across China before returning to his native land.

"Given the frequency with which Korea sent its envoys to China - on occasions including the ascension to the throne of a new king, royal birthdays and funerals, as well as important festivals - well-versed civil servants such as Nam were big assets to the Korean court," Ni says. "They also served as hosts to the Chinese envoy, often greatly impressing their guests, and in the process drew China and Korea even closer."

In the exhibition, two beautifully made file cases are on display, one demonstrating a stunning natural grain of wood and the other showcasing the lacquer work of Korean craftsmen. Both were used to carry royal documents and letters.

More telling of the literary diplomacy are the ingeniously designed portable ink-and-brush holders. When inspiration hit, a poet could wait no more. Inspiration had presumably hit many times when a Chinese (or Korean) official was touring in foreign parts accompanied by his Korean (or Chinese) counterpart.

Given that most leading painters during the Ming era were accomplished in the literary arts, it was only natural that the literary influences already mentioned seeped into the broader area of aesthetics. (In 13th-century China and later, paintings by men of words were much celebrated and dubbed literati painting.)

Regrettably, few examples are on view in the exhibition, apart from portraits, one of which shows Kim Yuk, a Korean emissary, standing under a giant pine tree. It was done in 1659 by a Chinese painter named Hu Bing.

"Plein-air portraiture, which started to gain popularity during the Ming era, was also adopted by Korean artists of the time," Ni says. "The casual style of dress, complete with a jade pin to hold the flowing garment together, exudes a sense of leisure and calmness often associated with literati painting."

The political careers of many Korean emissaries, Kim and Nam included, straddled two Chinese feudal dynasties, the Ming and Qing.

"The transition was in no way smooth," says Fan, the history professor. "For years the Ming empire was at war with the Manchu, a nomadic group from northern China that later conquered all of China and set up their own empire known as Qing. There was fierce debate at the Korean court as to which side to support. But one thing seemed clear: siding with Qing was a pragmatic decision and siding with Ming was a moral one. At one stage, Korean soldiers were fighting Manchu troops alongside the Ming army."

Yet when the dust settled, the Korean kings had no choice but to be practical. Korea was still a vassal state of China under Qing, but certain things changed.

"The once strong emotional, cultural and spiritual ties between China and Korea became tenuous," Fan says. "The Manchu rulers, members of a culturally less-sophisticated ethnic minority group, did not engender in the Koreans the same sense of admiration as their Ming predecessors had."

Envoys were still sent to Beijing by the Korean court, but under different names. Earlier they had been called chao tian shi, or emissaries to the heavenly kingdom. During the Qing era they were reduced to yan xing shi, meaning emissaries to Beijing.