Chinese-owned company sponsors $5.6 million renovation of an 18th-century London tower believed to have been inspired by a 15th century Nanjing structure

The Great Pagoda at Kew Gardens in London will be restored to its 18th-century splendor and reopen to the public next year, after a major renovation based on its historic ties with China.

The conservation project, sponsored by a Chinese-owned company, was started this year by Historic Royal Palaces, which is responsible for the care and restoration of the pagoda in partnership with the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew.

The project will see the pagoda returned to its original appearance, complete with green and white roofs, a gilded finial and 80 wooden dragons. It is sponsored by the House of Fraser department store, part of the Sanpower Group, which is headquartered in Nanjing.

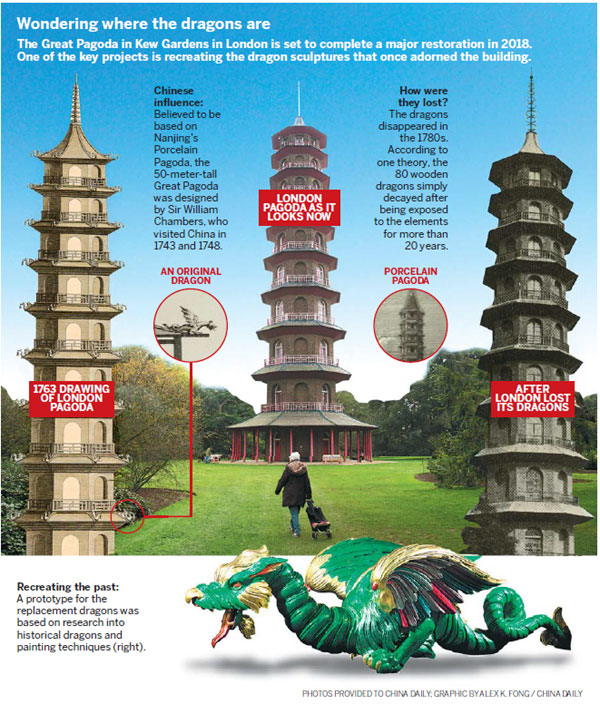

The restoration draws on the similarities between the Kew pagoda and Nanjing's Porcelain Pagoda, which is believed to have inspired English architect Sir William Chambers when he designed the Great Pagoda in the 18th century.

Chambers visited China twice, in 1743 and 1748. He designed the Great Pagoda for the British royal family at the height of Europe's craze for chinoiserie, and is thought to have been influenced by prints he had seen of the famous pagoda in Nanjing.

"For more than two centuries, the pagoda has stood as a symbol of enlightened interest and fascination between different cultures, and between Chinese and British culture in particular," said Rupert Gavin, chairman of Historic Royal Palaces, at the sponsorship signing ceremony in September.

Pagodas are revered in traditional Chinese culture as repositories of relics or sacred writings, and as places of contemplation. However, the Kew pagoda was not designed as a religious monument; instead, it was intended to give the British a window into Chinese civilization.

Believed to have been commissioned by Princess Augusta, the mother of King George III, the 50-meter-tall, 10-story tower was famously adorned with 80 brightly colored wooden dragons, and it offered one of the earliest and best bird's-eye views of London.

Matthew Storey, a member of the Historic Royal Palaces curatorial team, believes there were several reasons why a Chinese-style pagoda was built at Kew 255 years ago.

"First of all, Chinese design was very fashionable at the time, especially in gardens," he says. "Also, I think they were trying to bring the world to Kew, partly through exotic buildings and exotic plants, and exotic animals as well." He notes that there was a teacher-pupil relationship between Sir William Chambers, the designer, and the young George III, who was interested in a range of architectural styles.

The Great Pagoda was a hit with the public when it opened in 1762 at the Royal Botanic Gardens, but the dragons disappeared without a trace in the 1780s. Storey says the disappearance was probably a case of nature taking its course: "The dragons were made out of wood and they'd been outside for about 22 years. They may have decayed a lot."

The cost of restoring the structure will be about 4.5 million ($5.6 million; 5.1 million euros).

"With our parent company, Sanpower, based in Nanjing, it is fitting for us to support a building modeled on the Porcelain Pagoda at Nanjing, which has stood as a symbol of Anglo-Chinese exchange and cooperation for more than 250 years, says Frank Slevin, executive chairman of House of Fraser, the sponsor.

Because there are no surviving examples of the originals, solving the dragon puzzle has been a major part of the conservation project. The job called for the combined talents of a historian, a curator, a designer and a craftsman.

Craig Hatto, project director at Historic Royal Palaces, says the organization's research included tracking down every possible piece of dragon-form chinoiserie in Britain.

"We visited almost every historic house in the country, searching for similar dragons from the period. We also referred to the original design intent from Chambers' book. Once we had a rough idea of what we wanted the dragons to look like, we worked with a sculptor, Tim Crawley, to make a maquette (a preliminary model) of our dragon in clay," he says.

Simultaneously, the team worked on the color for the dragons, collaborating with a specialist in old painting techniques to devise a color scheme to match the descriptions of the fabled beasts, which are said to have been "iridescent".

Selecting the right material for the dragons on the upper section of the building proved time-consuming.

"We started off with timber and soon realized that it was too heavy for the building," Hatto says. The team then looked into selective laser-sintering material, a type of durable and lightweight 3-D printing material used in the construction of Formula One cars.

The restoration team collaborated with a number of universities to test the material to see if it would last on the building, according to Hatto.

"We undertook a whole raft of research, from testing paints, materials, weight and wind loading. It has also been tested for weather resistance in wind tunnels at Kingston University. All the information that came back suggested that this material was the correct one for the building. Hopefully this will mean our dragons will survive longer than the last ones did," he says.

Eight dragons on the lower section, which are about 2.3 meters high, were carved from African red cedar and painted in the style of the 1700s. None of the remaining 72, rising to the 10th floor and created from SLS material, is longer than 2 meters.

"Using tantalizing contemporary accounts and drawings, and taking inspiration from surviving 18th-century dragons in houses and museums, we'll ensure the new dragons are as faithful to the original design as possible," Hatto says.

The Porcelain Pagoda of Nanjing, in the former Bao'en Temple or "Temple of Repaid Kindness", was built in the 15th century. Revered as one of seven wonders of the medieval world, it became one of the best-known Chinese cultural artifacts in Western society, thanks to a description in China Memoirs, a book written by the renowned 17th century Dutch traveler Johan Nieuhof.

The tower quickly became an icon of the city, and Western missionaries reported on its beauty when they returned to their homelands.

Zhou Daoxiang, former curator of the Imperial Examination Museum of China in Nanjing, says the prestige enjoyed by the Porcelain Pagoda was illustrated by its recognition as one of the wonders of the world during the medieval era.

"The Forbidden City in Beijing and the Ming Palace in Nanjing existed at the same time as the Pagoda but they were not considered to be wonders. This obviously signifies the greatness of the Porcelain Pagoda at the time," Zhou says.

The pagoda was almost destroyed in 1856, during the Taiping Rebellion but, fortunately, the underground palace beneath the temple escaped the rebels' attention and was left intact. In 2008, Buddhist relics were discovered in the underground palace during an archaeological dig.

A replica tower of glass and steel, constructed on the original site, opened to the public in 2015.

Zhou says the ongoing restoration of the Great Pagoda at Kew has added significance now, given the destruction of the original edifice in Nanjing. The restored tower will offer a new window for people to examine the old-time splendor of the Porcelain Pagoda.

Contact the writers at: [email protected] and [email protected]

Cang Wei in Nanjing contributed to this story.