A rising number of Chinese are looking overseas to realize their dream of having a second child

Since China implemented its universal second-child policy at the beginning of last year, more than half of the 90 million newly eligible couples include women aged 35 or older, according to the National Health and Family Planning Commission.

Geng Linlin, deputy director of the clinical center at the commission's scientific research institute, says many of these women are past prime fertility so they find it difficult to have a second baby.

Fertility declines as women age, says Geng, who adds that nearly 90 percent of women aged 45 and older are unable to conceive or carry a pregnancy to full term. Moreover, women aged 35 and over stand a greater risk of miscarriage.

Other factors, such as environmental pollution, the widespread use of chemicals and exposure to electromagnetic radiation can also affect people's ability to reproduce, Geng says.

The World Health Organization estimates that 15 to 20 percent of the global population is infertile, which translates to about 15 million couples in China.

"Declining human fertility has become a social problem," says Wang Lina, a veteran fertility specialist at Peking University Third Hospital in Beijing.

She points to altruistic surrogacy - where the surrogate mother receives no financial reward - as a new option, particularly for women who are unable to become pregnant because of physical limitations but still long to have a second child.

At present, the only regulation governing surrogacy is the one issued by the commission, the nation's top health authority, in 2001. It prohibits medical facilities and professionals from performing any form of surrogacy.

Since then, the government has repeatedly launched raids on underground clinics across the country, but the "womb business" has never ceased completely.

However, largely as a result of the government ban, a rising number of well-off Chinese have begun to seek surrogacy services in countries where the procedure is legal and is performed under correct conditions.

Liu Li has a deformed uterus, which prevents her from becoming pregnant naturally, or safely carrying a baby to term, but she still produces eggs.

The 39-year-old Shanghai native decided to seek treatment in the United States after an attempt at underground surrogacy failed. Almost three years ago, Liu found a surrogate via an agency in the municipality, but the woman disappeared after the embryo had been implanted.

"I spent a large sum, but I didn't get my baby," Liu says, declining to give details of the amount she paid. She didn't report the incident to the police because "surrogacy is illegal, and I didn't want other people to know".

Inspired by ads she saw at the fertility clinic she had visited, Liu turned her eyes to California, where surrogacy is legal, and approached an agency in China.

In August 2015, she first met with her surrogate, Amanda, a Caucasian woman, in a fertility clinic in the California.

Amanda had already undergone a series of health checks and psychological tests to ensure that she would make a suitable surrogate, according to Liu.

"I liked her at first sight, so we signed the surrogacy contract quickly," she says.

After supplying the egg and her husband's sperm, Liu welcomed her baby daughter in June. As she and her husband are the child's biological parents, the baby's features are undeniably Chinese.

The entire procedure cost about $150,000 (138,000 euros; 119,000).

"It would have been cheaper and easier for us if surrogacy were allowed in China," she says.

Wang, from the Peking University Third Hospital, suggests the government should ease the ban to help women such as Liu to have a child.

Volunteer surrogacy is allowed in many countries, and commercial surrogacy is also available, especially in some US states.

"China should follow suit. But purely commercial programs must be strictly prohibited," says Wang, who has treated many young women who have had their ovaries removed because of diseases such as cancer.

"They are so young and shouldn't miss the chance of having their own child. Surrogacy can help them fulfill their dreams of motherhood," she says.

According to Wang Yifang, a professor at Peking University's Institute for Medical Humanities, legitimate surrogacy could also help couples who have lost their only child as a result of accident or illness, but the wife is now too old to conceive naturally or carry a pregnancy to term.

"Ethical concerns should not undermine reasonable application of this helpful medical procedure," he says.

However, Xue Jun, a professor of law at Peking University, advises caution, noting that there are many concerns surrounding surrogacy, including gender selection and the potential for legal disputes between surrogates and the intended parents.

Liu Ye, a lawyer in Shanghai, is strongly opposed to surrogacy. He cites potential health hazards facing surrogates, such as hypertension, uterine discomfort, abnormal fetal position, pain during delivery and even death.

Also, "poor women may be used as reproductive tools by the rich", he says.

In response, Wang Lina stresses that only altruistic, unpaid surrogacy should be legalized, and the procedure should be performed for women with clearly defined existing conditions, such as uterine problems, or who have failed with other fertility treatments.

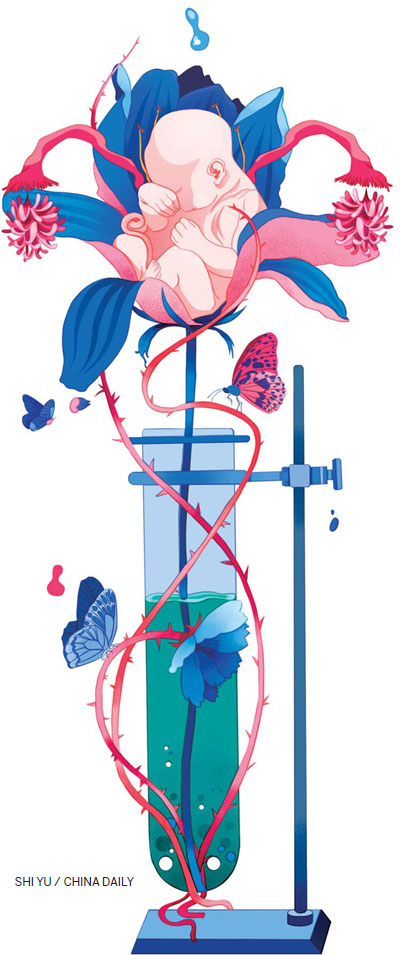

In gestational surrogacy, the intended parents use in vitro fertilization to produce an embryo that is genetically theirs and then have it transferred to the uterus of the surrogate. However, the likelihood of pregnancy varies widely because of the high average age of the donors.

In other cases, the surrogate also donates the egg. That was the case for Geng Le, CEO of gay social-networking app.

Geng's baby boy was born in San Francisco a few weeks ago via a Western surrogate.

"Both commercial surrogacy and egg donation is legal here (San Francisco). I chose a white surrogate so I could have a mixed-blood baby - they are usually prettier and smarter," he says.

Surrogacy is the only way for gay men to have a baby, but Geng says that even excluding the policy restrictions, affordability is a major concern.

A gay man in Chongqing, who declined to be named, says he would prefer to visit clinics in the US or Europe, but the "complicated procedures and high cost deterred me from the idea of surrogacy tourism". He doesn't think China will legalize surrogacy anytime soon.

In a potentially tricky development, the final amended Law on Population and Family Planning, which took effect on Jan 1 last year, didn't outlaw surrogacy. That omission, which means acting as a surrogate is not a crime in China, has led some commentators to claim the move demonstrates a cautious and prudent approach to the procedure.

However, in February, Mao Qun'an, a spokesman for the National Health and Family Planning Commission, reiterated that surrogacy remains a complicated issue in relation to the law and medical ethics.

"The commission will continue to crack down on such practices," he said.