Although more miscarriages of justice are being overturned than ever before, legal professionals say the sums awarded for the mental anguish endured as a result of wrongful imprisonment are inadequate, as Cao Yin reports.

In June, six months after their convictions for robbery, rape and murder were quashed on appeal, four men from Jiangxi province claimed State compensation for their wrongful conviction and imprisonment 13 years ago.

Three of the men have applied to the provincial high people's court for compensation amounting to more than 20 million yuan ($2.9 million) each, including 12 million yuan each for the psychological trauma they experienced. The fourth man has applied to the provincial people's procuratorate, but details of his claim are not known.

In April, the Supreme People's Court, the nation's top judicial body, issued guidelines to supervise procedures when courts handle claims for State compensation, saying the regulated process is a key step in the implementation of rule of law and the protection of human rights.

Tao Kaiyuan, vice-president of the top court, called on courts at all levels to improve the quality of case hearings to prevent flawed judgments, and ordered them to improve transparency in the procedures for handling applications.

According to the experts, a number of problems, such as the relatively low sums awarded and imprecise definitions of mental torment, must be resolved as quickly as possible.

Since the revision of the State Compensation Law in 2010, people subject to miscarriages of justice have been able to apply for compensation for psychological trauma.

However, many questions remain, such as how mental anguish can be quantified, and how to narrow the gap between compensation paid for wrongful imprisonment and for mental anguish.

"It's pleasing to see compensation awards rising, and that our increasing efforts to regulate criminal procedures in recent years have helped to overturn many wrongful convictions. However, the developments haven't gone far enough," said Zhang Xuefeng, a lawyer in Beijing.

Under Chinese law, the sums awarded as compensation for mental anguish are based on how much people have received for wrongful imprisonment or physical injuries sustained.

"That means raising the latter will be useful in improving the amounts paid for psychological damage," Zhang said.

Wang Wanqiong, a lawyer from Sichuan province, represented Chen Man, whose conviction was overturned last year. She was optimistic about the possibility of higher levels of compensation, but suggested that a wider range of items be added to compensation lists, such as expenses incurred during the appeal process, to balance the lower sums awarded for mental anguish.

Compensation rises

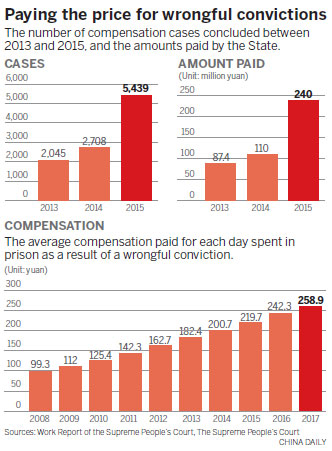

Since 2012, when China's current administration assumed power, the courts have overturned 34 miscarriages of justice.

Chen was awarded 2.75 million yuan after spending nearly 24 years in prison, having been detained in 1992, before being wrongfully convicted of murder and arson in 1994.

"Initially, we asked for compensation of more than 9.66 million yuan, but the sum we finally received was not as much as we expected," Wang said. "The major part of the award was for more than two decades of wrongful imprisonment."

Last year, the daily payment for wrongful imprisonment was calculated in line with average earnings in 2015.

However, in May, the Supreme People's Court issued the latest standard, which states that compensation will now be set at a fixed daily rate of 258.89 yuan.

"Ten years ago, the figure was about 80 yuan," Wang said, noting that although daily compensation rates have risen every year, the process has been too slow.

"The courts now have a clear formula to use, so it's easier for them to agree compensation for wrongful imprisonment," she said, adding that daily compensation levels should be tailored to individual circumstances.

"After all, the salaries of civil servants or business executives subject to miscarriages of justice are very different to those of regular workers," she noted.

A major development

According to Zhang, the lawyer in Beijing, the greater availability of compensation for psychological trauma is a major judicial development.

"It is the highlight of the revised law, because it indicates how the far the situation has progressed. Compensation for mental anguish is not only a comfort to the applicants and their families, but also an apology from the nation for mistakes made by the judicial system," he said.

Legal interpretations of the revised State Compensation Law suggest that payments for psychological trauma should not exceed 35 percent of the compensation paid for wrongful detention.

In recent years, one of the most-publicized miscarriages of justice was that of Nie Shubin, who was executed in 1995 after being convicted of rape and murder. In December, his conviction was overturned by the Supreme People's Court and his family was awarded 1.3 million yuan, the highest sum paid as compensation for mental trauma in China.

By contrast, Qian Renfeng, who spent 14 years in prison after being wrongfully convicted of killing a child with poison, received 500,000 yuan.

"Applying for compensation for mental suffering is like bargaining in a market," said Yang Zhu, Qian's lawyer. "In some cases, awards for mental anguish are arranged privately between the courts and attorneys, which I don't think is sensible or good for applicants," he said.

Chen received 900,000 yuan for the psychological trauma he experienced.

"The award accounted for almost 50 percent of the sum he received for wrongful detention," Wang said.

Both Wang and Yang believe it would be impractical to draw a clear line.

"During the application process, it is difficult to assess how much mental trauma an applicant has suffered. So it's not suitable to award compensation simply as a reflection of the time and effort a lawyer has spent on the case," Yang said.

He suggested that compensation for psychological trauma could be improved by raising the amount paid in daily compensation, and that diversifying the range of items for which people can be compensated would be a practical way of providing more money for mental trauma awards.

Culpability

Cheng Lei, an associate professor of law at Renmin University of China, is encouraged by the rise in the number of flawed convictions that have been overturned in recent years.

But a gap still exists between the amounts claimed and the sums awarded, and it will not be narrowed anytime soon, according to Cheng.

He believes China should follow the example of the United States, where applicants are allowed to sue individuals and departments responsible for miscarriages of justice.

"Identifying individuals and departments and then initiating lawsuits may be a more effective method, because in the US compensation awards in common lawsuits are usually higher than those for claims against the state," he said.

Zhang said some items included in applications, such as travel and hotel expenses, are not accepted by certain courts, which indicates a lack of clear legal regulation, indicating that the law should be improved.

The culpability of the judiciary and the police in miscarriages of justice also needs to be urgently addressed, he said.

According to Yang, the problem lies in incorrect implementation of the regulations. "The law clearly states that lawyers and court officials who contribute to miscarriages of justice should be held responsible, but it is extremely difficult to do that in practice," he said.

"Holding individuals to account for their mistakes would be an important way of ensuring that justice is done, and in promoting the rule of law," he added.

"Knowing that they could shoulder the blame would ensure that officials do their jobs to the best of their abilities and would also help to avoid miscarriages of justice."

Contact the writer at [email protected]