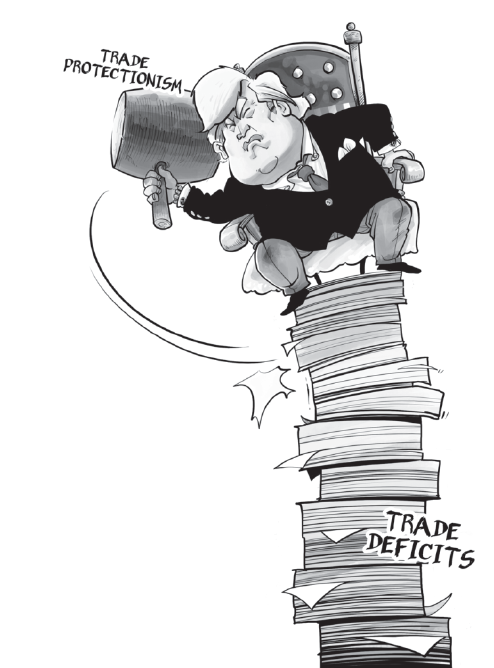

The Achilles' heel of Trump's economics

|

| CAI MENG/CHINA DAILY |

?US president-elect Donald Trump's economic strategy is severely flawed. He wants to restore growth via deficit spending in a country with a chronic shortfall in savings, which points to a further compression in national savings, making a widening of an already outsize trade gap all but inevitable.

That dynamic unmasks the Achilles' heel of Trump's economics, or "Trumponomics": a blatant protectionist bias that collides head-on with the United States' inescapable reliance on foreign savings and trade deficits to sustain economic growth.

The incoming Trump administration will not inherit a strong and sound US economy. The pace of recovery since the global financial crisis has been running at half that of normal cyclical rebounds-all the more disturbing given the massive size of the contraction in 2008-09. And savings, the seed of future prosperity, remain in woefully short supply. The so-called net national savings rate-the depreciation-adjusted sum of business, household and government savings-stood at just 2.4 percent of national income in mid-2016. While that's an improvement from the unprecedented negative savings position in 2008-11, it remains far short of the 6.3 percent average that prevailed over the final three decades of the 20th century.

Lacking in savings and wanting to grow, the US must import surplus savings from abroad. And the only way to attract that foreign capital is by running massive current-account and trade deficits. The numbers bear this out: since 2000, when national savings fell well below trend, the current-account deficit has widened to an average of 3.8 percent of GDP-nearly four times the 1 percent gap from 1970 to 1999. Similarly, the net export deficit-the broadest measure of a country's trade imbalance-h(huán)as been 4 percent of GDP since 2000, versus an average of 1.1 percent over the final three decades of the 20th century.

"Trumponomics" fixates on country-specific sources of the trade deficit, such as China and Mexico, but misses the fundamental point that these bilateral deficits are symptoms of the US' far deeper savings problem. Presume for the moment that the US closes down trade with China and Mexico-the largest and fourth-largest components of the overall trade deficit-through a combination of tariffs and other protectionist measures. Without addressing the US' chronic savings shortage, the Chinese and Mexican components of the trade deficit would simply be redistributed to other countries-most likely to higher-cost producers. The result would be the functional equivalent of a tax hike on beleaguered middle-class US families.

In short, there is no bilateral fix for a multilateral problem.

"Trumponomics" seems likely to exacerbate the US' savings shortfall. Analyses by the Tax Policy Center, the Tax Foundation and Moody's Analytics all indicate that federal budget deficits under Trump's economic plan are headed back toward at least 7 percent of GDP over the next 10 years.

Therein lies one of the most glaring disconnects of "Trumponomics". Getting tough on trade at a time when national savings is about to come under ever-greater pressure simply doesn't add up. Even the most conservative estimates of the federal budget deficit suggest that the already-depressed net national savings rate could re-enter negative territory at some point in the 2018-19 period. That would put renewed pressure on the current-account and trade deficits, making it extremely difficult to reverse the loss of jobs and income that politicians are quick to blame on the US' trading partners.

Ironically, in the coming era of negative savings, the US will find itself increasingly dependent on surplus savings from abroad. If the Trump administration takes aim at major foreign lenders-namely, China-its strategy could quickly backfire. At a minimum, there could be an adverse impact on the terms by which the US borrows from abroad; that could mean higher interest rates-h(huán)ints of which are already evident-and ultimately downward pressure on the US dollar. And, of course, there is the worst-case scenario of an escalating global trade war.

Protectionism, anemic savings, and deficit spending make for an especially toxic cocktail. Under "Trumponomics", it will be exceedingly difficult to make the US great again.

The author, a faculty member at Yale University and former chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia, is the author of Unbalanced: The Codependency of America and China.

Project Syndicate