May's tough search for trading partners

Even before she embarked on what turned out to be a controversial visit to the White House, British Prime Minister Theresa May said she planned an early trip to China that would focus on boosting trade.

There is a slight air of desperation in the May government's haste to reinforce ties with partners both old and new outside Europe as the economic consequences of the electorate's decision to quit the European Union sink in.

She was the first foreign leader to meet US President Donald Trump after his inauguration and secured what she described as his 100 percent commitment to the NATO alliance. However, Trump's subsequent move to ban travel from seven predominantly Muslim countries, announced the day that May left Washington, provoked an outcry in Britain as it did elsewhere.

From her next stop, Turkey, May eventually issued a late-night statement saying she did not agree with the policy, a somewhat lukewarm concession to Trump's critics that nevertheless knocked the gilt off her White House visit.

Since her return home, almost 2 million people have signed a petition opposing the invitation to Trump to make a state visit to the United Kingdom which she had announced in Washington.

State visits of the kind that President Xi Jinping undertook in 2015 routinely include a meeting with Queen Elizabeth as British head of state. Xi's visit included a state banquet which she hosted at Buckingham Palace.

In Trump's case, the petitioners said such a meeting "would cause embarrassment to Her Majesty".

As May was preparing what must now be viewed as her overhasty dash to the White House, she was already courting China. She revealed in an interview with the Financial Times in mid-January that she planned to travel there "relatively soon". She took the opportunity to recall Xi's speech at the World Economic Forum in Davos in January and China's commitment to free trade.

May followed that up with a Chinese Lunar New Year message to the Chinese in which she heralded a coming year of blossoming ties between the UK and China. "We receive more Chinese investment than any other major European country," she reminded them.

The Washington trip and a Beijing visit-"We are looking at what timing would be appropriate," she told the Financial Times-is clearly part of a twin-track policy to extend the UK's relationship with two of its biggest trade partners post-Brexit.

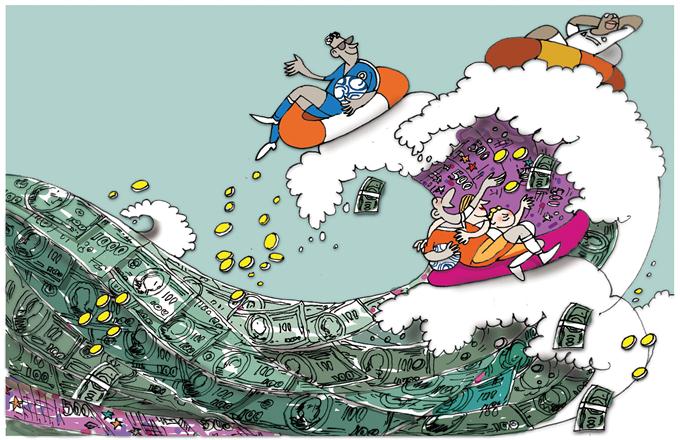

Her challenge is to see if the UK can do better in trade deals with the US and China outside the EU than it would have done as part of a giant 500-million-population trading bloc.

With Trump having broadcast an "America First" strategy that signals a return to protectionism, it seems unlikely Washington will be handing out too many special favors to its close but now diminished ally.

China's continuing commitment to free trade may offer a more promising prospect but, at the very least, May can expect some hard bargaining from Beijing.

In his interview with China Daily this week, Liu Xiaoming, China's ambassador to the UK, said 2017 would be a year for consolidating the "golden era" of relations between the two countries. Elsewhere, however, he noted a potential downside of Brexit for Chinese companies operating in the UK who faced uncertainties around Britain's relationship with the European single market.

Perhaps the greatest challenge facing May's twin-track policy toward Washington and Beijing is the uncertainty about the state of future relations between those two capitals.

Trump's threats of a trade war with China may turn out to be overblown rhetoric once the realities of office take hold. Alternatively, the current antagonism could further worsen with unpredictable consequences.

The UK could find itself caught in the middle. In former times, Britain might have emerged as an honest broker to calm tensions in a troubled world. In the 21st century, that is a role it might have been in a more influential position to play if it had remained within a wider European alliance.

The author is a senior media consultant to China Daily.