|

|

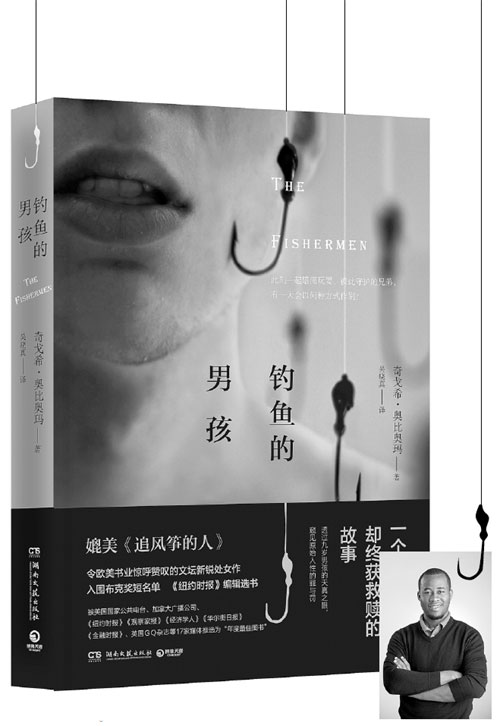

A Chinese version of Chigozie Obioma's The Fishermen has recently come out. [Provided to China Daily] |

A tale of brotherly love and murder portrays colonial past

The favorite Chinese writer of the Nigerian author Chigozie Obioma right now is Yan Lianke, who came up with what he calls spiritual realism to represent his pursuit for "invisible truth" in his novels. Obioma says that in his novel The Fishermen he tried to represent a kind of realism that may seem superstitious and unbelievable to Westerners or Asians, something he calls African realism.

Last year Obioma gained much attention in the West when The Fishermen, his debut novel, was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in Britain and included by many media such as the Economist, The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times on their lists of best fiction of the year.

The novel, narrated from double perspectives of Benjamin Agwu, 10, who retells the story in a court of law, and Benjamin Agwu, who relates events two decades later ("Now that I have sons of my own"), tells how a tragedy involving two brothers ruined the noble ambitions of a middle-class Nigerian family. A Chinese version has recently come out.

Obioma is one of few African writers known in China, and his first novel is a difficult read, even if he writes in beautiful English and the translation is readable. The story is clear, but there is something hidden beneath the surface that is hard to grasp for anyone with no knowledge of Nigerian history, its politics in the 1990s when the story happened and the very different African culture.

A changed person

The story unfolds in a middle-class family with Mr and Mrs Agwu and their six children, five boys and a girl, living in Akure in the country's west.

At first Mr Agwu, who works for the Central Bank of Nigeria, is transferred to Yola, a town more than 1,000 kilometers to the north, leaving his wife and their children behind.

Without the guidance of their father, the four oldest boys, Ikenna, Boja, Obembe and Benjamin, find a new pastime, fishing in Omi-Ala, Akure's mother river.

It had provided food and clean water for the earliest settlers in the town and, as is common in Africa, locals came to worship it as a god.

But when European settlers arrive, the Bible in hand, everything changes. People are converted to Christianity and people turn their backs on the river, seeing it as a place of evil, and children are forbidden from even going near it.

A neighbor finds out about the boys' fishing adventures and she tells their mother about them. When the father comes back at the weekend he whips the four boys, Ikenna, 14, suffering most.

Thereafter, Ikenna is a changed person. A mad man named Abulu known locally for his powers of prophesy says Ikenna will be killed at the hands of a fisherman. Ikenna then suspects that it is his closest brother, Boja, who will commit the deed.

Despite the best efforts of Ikenna's mother to console and reassure him, he is consumed with fear every day. Eventually the two brothers come to blows and Ikenna is killed. Consumed by remorse, Boja, then throws himself into the well in the family's yard and drowns. The two younger brothers Obembe and Benjamin then take revenge, killing Abulu. Obembe runs away and Benjamin is sentenced to six years' prison.

Eventually Benjamin returns home after being released six years later.

Asked why Ikenna would have believed Abulu's prophesy and why he would not have fought against his fate, Obioma says: "I see why a non-African might take a grace against the depiction of the boys' reception to the prophecy. Indeed, I must say that in Africa our worldview is radically different ... .

"What might seem superstitious or unbelievable to the Western or Asian might seem completely realistic to the African. This is what I call African realism."

This may also be Obioma's interpretation of the political situation. In the postscript of the Chinese version he says: "With this novel I hope to comment on the social and political situation in Africa, especially in Nigeria."

Emotion of being homesick

Obioma was born in Akure in 1986. His family bears similarities to the family of the novel. His father worked for the Central Bank of Nigeria, and the middle-class family had access to most of the things that made children comfortable, at least on the basic level.

Obioma has been writing since he was about nine years old. Apart from a few short stories, most of his works remain unpublished.

The idea of The Fishermen came from "the emotion of being homesick" when he was living in Cyprus in 2009, he says.

He especially missed his brothers and sisters, with whom he had had a close, sharing upbringing. One evening, during a phone conversation with his father, Obioma learned that his two oldest brothers, who had been serious rivals as they grew up, were drawing close to one another.

"I started to think about that closeness and what it means to love your brother, and also what if this time never came, what if they never came to understand this love of brother and closeness of family. That reflection brought the idea of a close-knit family that is destroyed."

He had been reading The Great Civilization, in which Will Durant said again and again that "a great civilization cannot be destroyed from the outside; it has to come from within". It influenced Obioma deeply.

"I was thinking of what could come from the outside and destroy a family - that is where the germ of the idea came from."

The story is dark, disturbing and shocking, but Obioma says "the heart of the book lies in the love between the brothers".

In a broader sense, the novel is the author's comment on the social and political situation in Nigeria in the 1960s.

"The madmen are the English, and the sane are the Nigerians (three ethnic groups sharing nothing in common formed a country)," he says in the postscript. For him, Abulu the madman represents those who penetrate into other people's life and create chaos and misery for people just by speaking, and the Agwu family represents a major ethnic group in Nigeria.

In 1960 Nigeria obtained independence, but the country's ethnic groups were far from united. Six years later one of the three main groups, the Igbo, led an attempt at obtaining independence for eastern Nigeria, breaking away to form the state of Biafra. After a civil war that lasted two and a half years at the cost of hundreds of thousands of lives - and in which Nigeria had the backing of Britain, its former colonial ruler - Biafra was drawn back into the Nigerian fold.

In that light, the symbolic meaning of the characters in the novel and the inevitable outcome of the fight and deaths of the brothers become clearer.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|