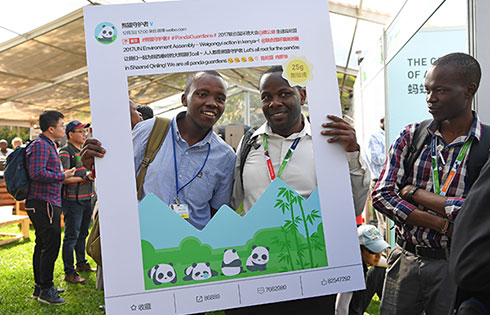

Myths about China in Africa debunked

Is China really trying to grab up farmland in Africa to deal with its own food security challenges, as some recent reports have suggested?

An American researcher says no.

Professor Deborah Brautigam, director of the International Development Program as well as the China Africa Research Initiative at Johns Hopkins University's School of Advanced International Studies, argues in her new book that the conventional idea that "China is grabbing land from Africa" is too much exaggerated thanks to inaccurate media reporting.

Her book, titled Will Africa Feed China, challenges widespread beliefs about China's agricultural engagement in Africa that have shaped the conventional perceptions that China is acquiring large amounts of farmland in Africa.

Brautigam writes it was a chief economist at the Africa Development Bank who first raised the idea in a 2012 article, saying that "China is the biggest land-grabber in the world and in Africa".

She did not name the economist. "I did not want to embarrass him," she said with a laugh.

Since 2011, Brautigam has noticed that there have been many media reports about China setting up big agriculture corporations and programs in Africa. The content of these reports includes Chinese agribusiness companies pursuing investment in Africa and Chinese government plans to send millions of Chinese farmers to Africa.

Brautigan found many of the figures to be exaggerated.

"It just irritates me," she said. "I am a person in the field. I know some of the numbers of the agreements, it just cannot be possible."

Brautigan has written other books about China and Africa, including The Dragon's Gift: The Real Story of China in Africa and Chinese Aid. She has been researching cooperation between China and Africa since 1983.

Most of the field research for her new book was done during her frequent visits to African countries such as Mozambique, Cameroon, and Ethiopia from 2007 to 2014.

Brautigam tried to contact both sides of the cooperation agreements: the Chinese investors and local governments in Africa, sometimes the farmers in Africa who are involved in certain programs.

"It just turned out that they are not true," she said.

Most of the false reporting comes from English language media in Western countries and in Europe, such as the Daily Mail.

"Many of them come out with very eye-catching headlines and for many of the reports, the media did not track down the real story," Brautigam said.

"In fact, most of the Chinese media reporting has been quite accurate," she said. "There was only one piece by the Chinese media I remember that was not true."

In the book, Brautigam outlined four widespread beliefs about Chinese agriculture engagement in Africa: the Chinese have acquired areas of farmland; the Chinese are growing grain in Africa to export to China; the Chinese will send large numbers of farmers to settle in Africa; and the Chinese government is leading in land grabbing efforts through state-owned firms.

With years of ground research visiting farmlands in Africa and talking to stakeholders from both countries, Brautigam explored the evidence behind these beliefs.

She found that most of the agribusiness investment from China to Africa is from private-sector companies in China, not the government.

"Some of the key reasons why many announced investments were not carried out on the scale as planned were poor infrastructure, coups, contentious elections and even civil wars," she said.

One example was a sensational story about the Zambezi Valley, when a website hosted by the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology published a short article on China's growing ties with Mozambique, which was later quoted and reported on by media such as the Daily Mail, under headlines like: "How China is taking over Africa, and why the West should be VERY worried" in 2008.

The author reported that China was giving Mozambique $2.3 billion to build Mpanda Nkua, a large dam on the Zambezi River, and the two governments had signed an agreement to move 20,000 Chinese settlers to the valley to run farms.

Brautigam said she was puzzled and intrigued by those figures. In June 2009, she took a trip to Mozambique and learned that the investment never really turned into reality.

"Western media, especially those stationed in Africa, tend to have ideological biases towards whatever China is doing globally," said Wenshan Jia, a professor of communication studies at Chapman University in California and Renmin University in China. "They may also have been due to cultural misunderstandings on the part of the media."

"Yet another reason behind such biased reporting run wild is that China has not invested enough on media in Africa to tell the whole picture of her own story," Jia said.