|

Shi Lansong paddles three of his pupils across the Big Dragon Lake, in the far suburb of Nanning, saving them more than one hour trek over a steep hill. [Photos by Huo Yan/China Daily]? |

Photo Slide: Shimmering with hope

For 25 years, teacher Shi Lansong has been ferrying his pupils safely to school, declining opportunities to better his own life. Raymond Zhou reports.

"Meet me by the lake - at 6 am."

If you simply look at the setting of this rendezvous, you might be forgiven for thinking this is going to be a romantic tryst. But Shi Lansong, 45, is talking to a bunch of 8-year-olds, and he says these words every day.

Shi is their teacher. But to reach the two-room school on the other side of a hill, Shi has to ferry his pupils across a lake, or they have to trek more than an hour over the steep hill.

The lake, named Big Dragon Lake, has the same physical features of karst-rich Guilin, but to Shi and his pupils it provides a shorter route - albeit one fraught with dangers.

As a volunteer ferryman, Shi Lansong is responsible for the safety of Wei Yufei and Chen De, two first-graders, both aged 8, and Chen Yanzhi, 7, and Chen Yu, 5, both preschoolers.

He used to carry eight kids - a maximum of 13 at a time - from different villages around the lake, which could take as many as four trips. Shi has done this for 25 years, making a total of some 18,000 trips.

Not only is Shi not paid for this work, he has to shoulder the cost of the canoe. So far, he has used up eight of them, with each one lasting about three years. The first three were made from trees in his backyard. Then, he had to buy the timber, at a cost of 300 yuan ($44) a piece at first - when he was making 120 yuan a month. Later, the price of timber rose to 700 yuan, but he was earning only 200 yuan.

Saving lives

|

One of Shi's 18,000 trips across the lake. |

Life in this waterfront village seems to be long spells of monotony, punctuated by the occasional occurrence of high drama. Hours on the lake have turned Shi into a timely savior in a few cases: In 1992, a couple touring the lake fell in and would have drowned if not for Shi. In 2003, he rescued a local 4-year-old who sank two meters into the lake. When Shi pulled the boy out, he was already unconscious. Shi used CPR to resuscitate him. The biggest rescue came in 1997 when 17 high school students from another village squeezed onto one boat and it capsized in the middle of the lake, 13 m deep around that area. Half of them could not swim. Shi happened to be close by with his 5-year-old son on his canoe. His bravery in helping with the successful rescue was reported in the local paper.

Given the flimsy nature of his boat, it is amazing that Shi has a perfect safety record. His biggest "adventure" happened in 2004 when a storm whipped up on the lake while Shi was carrying six children across. By the time it reached the center of the lake, water started gushing into the boat. "We were all very scared," Shi recalls. He tried to dock nearby, but the wind along the shore was fiercer and it blew the boat farther and farther away from the village where the school is situated.

From this incident, Shi drew the lesson that he should carry no more than two or three kids on each trip, and he should mix big kids with smaller ones.

When the kids grow up, they will find plenty of reasons to be grateful to Shi Lansong. Right now, it is their parents who entrust them to him and thank him for his long-lasting altruism.

When asked what his next dream is, Shi hesitates and replies: "To get one of those bigger boats that can accommodate a dozen people at once, powered by a steam engine and with sheet-iron covering the hulk."

Alas, the price tag is 20,000 yuan, well beyond his reach.

Poverty in heaven

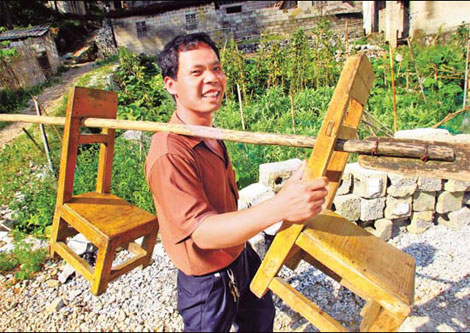

|

Shouldering two chairs by his paddle, Shi heads for the school in which he teaches. ? |

Big Dragon Cave Village is one of many that surround the picturesque lake, which is a mere 25 km from the county town of Shanglin. Yet it is barely accessible by road. Shanglin is administratively part of Nanning, capital of Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region, and is more than two hours away by car.

Shi Lansong and his pupils may seem to be tucked away in the magnificent backyard of a major city, but in fact they are worlds away from the amenities of the modern world.

The lake was formed in the 1950s when underground rivers were dammed to make a reservoir and prevent floods. This resulted in the locals losing land for farming and having to rely on government subsidies for subsistence. When able-bodied villagers left in droves for big cities to look for better jobs, their children were left behind with the grandparents. Many opted to stay out of school to avoid the treacherous journey to school.

"It is better for them to go to school," says Shi. Although he does not harbor the illusion that many of his pupils will end up in college and then with high-paying jobs, "even if they work in a factory, those better educated tend to get better jobs," he says.

Personal story

Shi knows first hand the importance of a good education. In 1985, he failed the national college entrance exam by only a few points. He had to take up the post of a replacement teacher in his home village, earning a meager 36 yuan a month at first and, later for a long time, 200 yuan. When his brother Shi Lanjun came for a visit in 1993, Shi was making 120 yuan.

Lanjun said, "You'd better come with me to coastal Guangdong. I can help you get into a garment factory with much higher pay."

Lansong was tempted. "But what about those kids? Who is going to ferry them to school and back?"

He understood the anxiety of the parents because his own son was a toddler then.

Remaining a village teacher meant a lot of sacrifices. The son, 19, now works as a migrant worker in Nanning. "He wanted to go to a technical school after junior high. But I was earning 250 yuan. How could I afford it?"

Shi's house is also testimony to his hardship. Of the 32 households in the village, Shi's, built in 1995, is the shabbiest, a simple one-story house with two small bedrooms. The walls are not painted. The roof is used as a terrace for drying corn and fish. The neighboring buildings are two-story houses with gleaming tiles, some spacious enough to take in a township government.

What little money he made was often spent on his pupils. He would buy them stationery. Once a student was convulsed with a stomachache. Shi rushed him to a nearby clinic and put down the 300 yuan in deposit required for medical service.

Shi's selflessness made it hard for his wife to keep the family running. For a while she threatened to go back and live with her parents. But ultimately she stood with him through the most difficult times.

When Shi was officially hired as a teacher in 2005, his salary rose to 1,000 yuan and has been growing steadily. He is constantly gripped with guilt about his older son, and swears to give his younger son, Shi Fuchuan, 15, the proper education he deserves.

He is currently in a boarding school, coming home only for the weekends. He excels in Chinese language and writing. "As long as he can get into college, I'll pay for it," says the father.

"My dad has always taught me to have sincerity, integrity and responsibility," says the son.

Zheng Yan and Huang Zhaohua contributed to this story.