And then there were some

Its scientific name is Nipponia nippon, in reference to Japan, where Western naturalists first came across the species in the 19th century. In its heyday its habitat stretched from Russia to China, Japan and the Korean Peninsula. In China they lived in Heilongjiang province bordering Russia and as far south as Taiwan.

The Japanese once fiercely hunted and killed the bird, coveting its beautiful feathers and the profits from handicrafts made of them.

Until the 1920s many believed that Sado Island, about 32 kilometers west of the main island of Honshu, might be the country's last habitat for crested ibises.

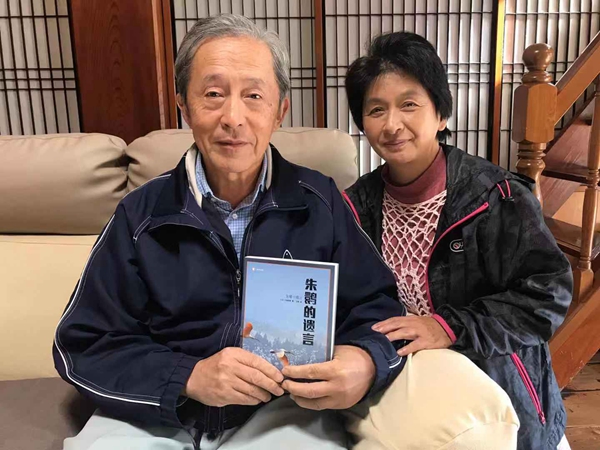

Haruo Sato, a high school teacher who taught bookkeeping, typing and calculation, was astonished at the bird's beauty when he first saw one flying over a terrace at dusk in November, 1947, one year after he had started tracking crested ibises.

To manage this, Sato went out at 4:30 am almost every day, rain or shine, bicycled 10 kilometers for about 50 minutes, rode up a mountain for about 600 meters, laid down the bike, and climbed the mountain for another 40 minutes.

He observed the bird with the help of a telescope and a camera. At the time most Japanese knew little about the bird. With years of endeavor, one of the many things Sato learned about the bird was that it liked to forage in quiet rice paddies.

Kobayashi's book begins by recounting what happened one winter's morning in 1950, when Sato was 31.

As the sun rose, a crested ibis appeared, strolling in the field, staring at the water's surface. Suddenly it stuck its beak into the water, its head down and a moment later out of water with a splash.

Now, in its beak the ibis held a loach by the waist, mud still hanging from the beak's red tip. As the loach struggled, the bird jerked its head several times before sucking in its breakfast.

Sato witnessed that as the ibis flapped its wings and water splashed in all directions, more of the birds came, as if being summoned by a yell of, "Food! Come on here. It's safe."