And then there were some

Crested ibises are wary of people and of birds such as crows and eagles. When the earliest intruder's companions hunted for food, it surveyed the terrace and inspected the surroundings, as if on lookout.

Once the young ibises had eaten, two began playing vigorously in a tug-of-war with a straw, shaking their heads heavily. A few feathers at the back of their heads stood high and an adult bird intervened to mediate.

About 20 minutes later, the birds left with their tweets resonating throughout the valley.

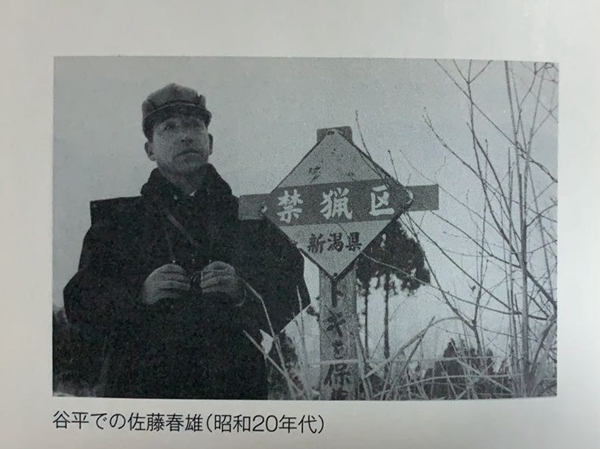

After writing down what he had seen, Sato went to a field where the crested ibises had previously stayed. There he expertly collected what for him was treasure-the birds' droppings. In his first year of observations he collected more than 1,000 specimens.

By extracting indigestible material in the excrement day after day, Sato finally worked out the birds' diet: grasshoppers, locusts, loach and crucian carp in spring, summer and autumn, and little river crabs in winter, the latter because when the water fields were covered with snow, the ibises had to find gurgling rivers or streams to forage in instead.

Sato's room was always smelly, he sometimes forgot to eat and stayed out for the night. He was unwilling to spare time for farm work during autumn harvests, and barely had time to take care of his children.

Over the years his family became accustomed to his unusual ways and began to understand and support his passion for the crested ibises, but he was the butt of humor among many of his students.

Throughout his life, he gave up any chance of career promotion so he could devote himself to the birds.

It was thanks to his perseverance that people learned that crested ibises' feathers change color with the seasons, a revelation that dispelled a misconception that there were two kinds of crested ibises, one white and the other charcoal gray.

One hundred crested ibises were estimated to be left on Sado Island in 1934, and their habitats covered almost every corner of the island, but the number plunged during and after World War II. By 1950 there were 35 left, by 1952 there were 24 and by 1956 just 13. However, that year crested ibises were also found on Noto Peninsula, about 100 kilometers southwest of Sado.

The bird's decline can be attributed to the felling of trees and the widespread use of pesticides. In 1966 parasites and organic mercury from pesticides were found in the corpses of two crested ibises, the toxic substance having entered their bodies through loaches in the rice paddies.

One of Sato's most important allies in protecting the birds, Koji Takano, once told him that the crested ibis was just one element of its habitat so they could not focus their efforts solely on preserving it without also considering its connection to nature.