A generational legacy set in stone

The time-consuming process of carving a stone while retaining its natural textures and unique beauty can be used as a metaphor for an education that helps each individual pupil to achieve their full potential.

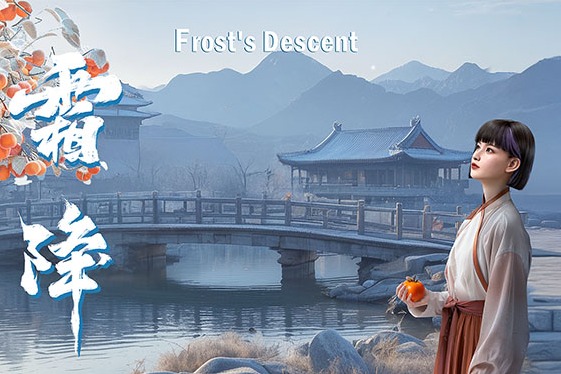

Anhui province is good at both. As the place where the "four treasures of the study", namely, the brush, ink stick, paper and ink stone, originated, it has a tradition of pushing education to the fore since ancient times.

The ink stones produced in Anhui's Shexian county, which are made of a local black slate, are highly reputed for their ability to keep the ink wet for a long time and their exquisite engraved patterns full of intricate details.

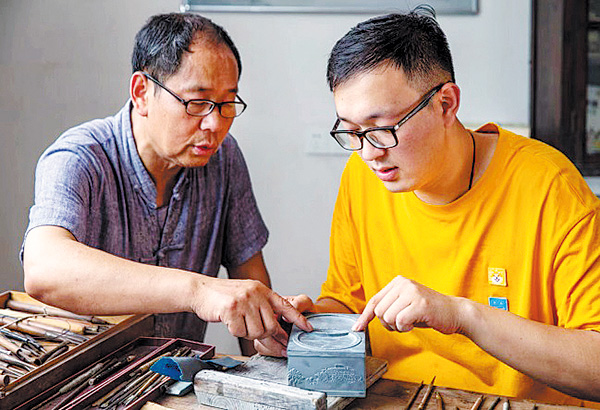

Making a quality ink stone requires rigorous craftsmanship, consummate skill and passion for traditional culture. That's what Hu Qiusheng, an ink stone carver and engraver in Shexian, has pursued and passed down in his family.

Four decades of handiwork has deformed his fingers, but won him many awards in the field of crafts and fine arts. He has trained hundreds of craftsmen, dozens of whom have become inheritors of the intangible cultural heritage at the municipal or provincial level.

Hu's own company, one of the county's leading ink stone producers, also initiated and sponsored competitions that encourage younger generations of ink stone makers to display their skills and further develop the craft.

In the late 1960s, he first got to know about the craft from his father, who worked at a local factory that used and produced ink stick grinding stones. Back then, a single ink stone could sometimes be bartered for a metric ton of wheat.

"I knew it was very valuable," Hu says.

As he entered middle school, he became fond of painting, especially drawing sketches.