The sound of our history

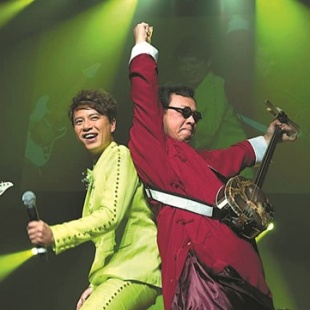

Zhao Taisheng has a mission to keep the traditional instrument, sanxian, alive, Xu Weiwei reports in Hong Kong.

Musician Zhao Taisheng calls his favored instrument — the sanxian, or three-stringed lute — a voice for his emotions, a vehicle for charm and honor, and a ticket to an eventful life.

Zhao is the principal sanxian player in the Hong Kong Chinese Orchestra (HKCO), and has devoted his career to perfecting his skill on the instrument and preserving this ancient art. He regards the sanxian as an important part of Chinese folk music tradition and warns against its contemporary marginalization.

Like most folk traditions, it is difficult to trace the origins of the sanxian. By some accounts, it may date back to the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC). Images of similar instruments can be found in a Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279) sculpture, and the characters sanxian, which literally mean "three strings", first appeared in a Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) text.

The sanxian has a striking appearance: a long, thin neck attached to a small, rounded sound box covered with snake skin. It is usually around 120 centimeters long, and has three strings stretched over a fingerboard, which allows for extensive glissando, or the glide from one pitch to another.

It has a dry, loud, percussive sound — clear, powerful, sonorous and expressive. "The sanxian is the'guts' of a Chinese folk music band," Zhao says.

He explains that, in the early decades of the 20th century, the number of students of the sanxian was similar to that of those studying other traditional Chinese string instruments such as the pipa or guzheng. However, the instrument began to lose popularity with the adoption of Western orchestral styles, which preferred softer harmonies.

For Zhao, however, the lure of the sanxian is timeless, and as the country's tastes are swiveling back toward traditional forms, he and his ancient instrument are increasingly in the spotlight.