The master of translation

Yan Fu's informed adoption and adaptation of modern Western and classical Chinese ideas changed the way a generation thought, Fang Aiqing and Hu Meidong report in Fuzhou.

According to Wang, this was Yan's way of attracting the attention of the conservative intellectuals and the social elites.

Because the great translator saw many similarities between the East and the West, he would sometimes replace Western mythology and legends with ancient Chinese stories for easier understanding, and frequently made reference to classical Chinese texts and applied their ideas to explain Western concepts.

In notes that are comparable in length with the translated text itself, Yan introduced the lives and deeds of ancient Greek and Roman thinkers as background information to help readers understand the original text.

Tao Youlan, director of Fudan University's translation and interpretation department, says that Yan's ancient-style prose is so beautiful and concise that, like salt dissolving in water, the meaning of the original text is properly conveyed.

She has initiated a program, inviting eight scholars of translation studies from eight universities across the country, in which they will guide students to read and appreciate eight of Yan's translated works. They will explore in detail how Yan polished the translated text by using his particular rhetoric and strategies, and how he conveyed the original ideas in his translation.

The focus of the program is not only on language itself, but also on the ideas Yan's words contain and the social impact of his translations, Tao adds.

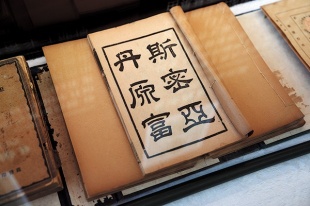

It was Yan, in his translation notes for Tianyanlun, who initially elucidated the three norms of translation — faithfulness, expressiveness and elegance — that professionals pursue today as their ultimate goal, and Tianyanlun is a reader-oriented model.

During an interview with the Shanghai Review of Books in 2019, Shen Guowei, a linguistics professor at Japan's Kansai University and author of two monographs on Yan's translations and thinking, called for attention to the fact that when Yan translated these Western works about social sciences, neither the subjects, nor the related concepts and terms, existed in China.

Yan once said that he would think for days, or even months, on the translation for a single term and often borrowed words from archaic Chinese expressions or created new words of his own. Then, there was still the issue of how to tackle the differences in sentence structure between the languages.

However, in his later academic translation efforts, Yan continued to explore and adjust his strategy, while facing self-doubt and setbacks — the inevitable fate of all pioneers. Shen says that research into Yan should view his translations as a whole, place him in the historical background and social environment of his time, and take his own changes of mind into consideration.