The master of translation

Yan Fu's informed adoption and adaptation of modern Western and classical Chinese ideas changed the way a generation thought, Fang Aiqing and Hu Meidong report in Fuzhou.

Willful introduction

Each of Yan's translations has a clearly defined practical purpose and function, says Ouyang Zhesheng, a history professor at Peking University.

Yan's understanding of modern Western civilization reached an unprecedented level, and his introduction of the Western principles of the natural and social sciences was valuable and meaningful in guiding China's social and political reform in his time, Ouyang says.

Schwartz wrote that Yan pioneered advocating the notion that "the problem of China above all was a problem of science".

Yan believed that the Chinese should start by mastering the basic scientific principles of the West before promoting gradual, steady reform to avoid drastic sociopolitical upheavals.

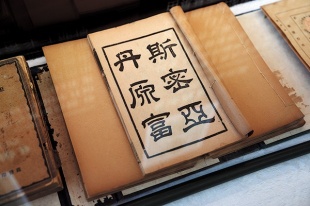

He called his translation of On Liberty, by British philosopher and economist John Stuart Mill, Qunji Quanjie Lun, which translates as "On the Rights and Limits of Society and Individuals". He argued that given China's situation at the time, individuals should first and foremost strive for the group interest in order to protect themselves.

This idea of placing the interests of the nation and society above all is also evident in his translation of Scottish economist Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations, and he also covered Spencer's The Study of Sociology under a cloak of Confucian thought to express the same idea, even though this partly contradicted with the author's viewpoint.

While translating French political philosopher Montesquieu's The Spirit of Laws, Yan sought to provide a reference for what he thought could serve as a reform of constitutional monarchy.

He fully evaluated Chinese and Western civilizations, on the basis of which he formed his own idea about mutual learning, Ouyang says.

"He was straightforward about facing reality and was targeted. He remained critical, and did not engage in empty talk," Ouyang says, adding that Yan's spirit represents the Chinese people's exploration and endeavor to transition Chinese culture from traditional to modern, which is still valued today.

Yan paid close attention to international affairs and recognized the importance of diplomacy. Based on extensive reading, he wrote articles analyzing the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05) for the public, and provided information on World War I to policymakers.

He also endowed traditional culture with new connotations. For example, he reinterpreted the I Ching (Book of Changes), Tao Te Ching and Zhuangzi, by applying Western perspectives, in the belief that only in this way could classical wisdom be better applied to the society of his day.

Disappointed with Western civilization in his later years, Yan came to re-evaluate Confucianism and rediscovered the modern significance in the thinking of Confucius and Mencius.

Unlike Schwartz, who describes Yan as a Faustian figure who abandoned core Confucian values to embrace Western thinking, Huang says that Yan's outlook was rooted in Confucian and Taoist traditions, and was therefore the fruit of a convergence of the East and the West.

That determined his understanding and misunderstanding of the European works he translated and commented on, Huang adds.

The Taiwan scholar notes in particular that Yan was aware that his countrymen would tend to accept Western ideas that were consistent with their existing traditions, and his deliberation was obvious.

"China has marched along a different path to the West in establishing the authority of science. …Heralded by importing evolutionary theories, the introduction of Western science didn't sever the origins of traditional Chinese values, nor did it lead to skepticism or moral relativism," Huang says.

"The uniqueness of Chinese modernization lies in the continuity of traditional ideology and its consistent pursuit of the combination of value rationality and instrumental rationality. Resulting from long-term historical evolution, this also prompts us to consciously build a modern civilization with Chinese characteristics today," he adds.

Yan's granddaughter Cecilia Yen Koo, who is 99 years old, wrote in her letter to the commemorative event on Jan 5 that there was no doubt that as a result of her grandfather's introduction, and after further comparison, review and integration by the later generations, the concepts and doctrines of the East and the West have been picked over and applied in different scenarios and environments in China, and have played a role in the country's development and modernization.

She suggests that it might be possible that the many precious legacies her grandfather left behind, after review and study, can provide fresh thinking for future solutions.