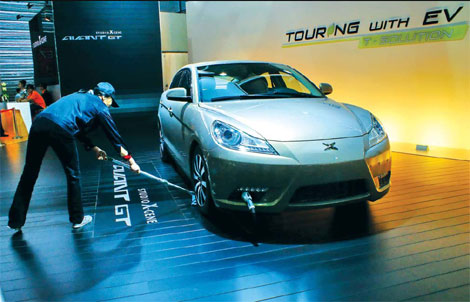

Bumpy road ahead for electric cars

Updated: 2012-04-23 08:03

By Yale Zhang (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

The government hopes to have 500,000 all-electric and plug-in vehicles on the road by 2015. However, problems like insufficient infrastructure, a technological bottleneck in battery production and prohibitive costs must be tackled to clear the way for the sector's development. [Photo/China Daily] |

When China's State Council released the energy conservation and new-energy vehicles plan on April 18, it stated that pure-electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles will be the new technological paradigm in the future by 2020.

This roadmap was challenged by many people in 2011 because it excludes hybrids that are not plug-ins from receiving major subsidies. The final plan still contains this exclusion, and the target for the number of electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles in operation by 2015 remains at 500,000 units.

This high target excludes conventional hybrids, which makes it hard to achieve in three years.

By now, it looks like that many industry insiders are not as optimistic as the planners. Because obstacles to the development of electric vehicles still remain - the battery bottleneck, the prohibitively high price of this technology and the lack of charging infrastructure - there is reasonable doubt about how to achieve this goal.

China's new energy vehicle development formally started in 2009, when China started the "Ten Cities, Thousand Vehicles" demo project. Under this program, each city selected should employ 1,000 new energy vehicles in municipal fleets.

In 2009, the central government selected 10 cities for the demonstration. And in late 2010, the list was expanded to cover a total of 25 cities. The project should hit its middle stage by the end of 2012, and there is no further clear planning beyond 2012 at this time.

The major assumption of the target of 500,000 new-energy vehicles by 2015 is that the government will directly purchase a large volume of electric vehicles as part of government fleets. This actually overestimates local governments' fiscal capacity as well as their intention to buy non-local electric cars.

As of the end of 2011, many cities had less than 100 electric or plug-in hybrid vehicles, and there have been few plans put forth to increase purchases.

Many cities are reluctant to spend local funds on products from other cities. Among the 25 demo cities, some large cities have made very slow progress because they lack a strong electric vehicle production base or capabilities, which gives them little motivation to purchase cars from elsewhere.

Another most popular rationale behind the government's high target is that both the central and local governments will subsidize individual buyers at around 100,000 yuan for purchasing electric or plug-in hybrids. By contrast, conventional hybrids or other energy-saving vehicle get only 3,000 yuan. This large amount of money will encourage buyers to purchase electric vehicles.

While 100,000 yuan sounds like a lot of money, it still may not provide a strong enough incentive, given pure-electric models usually cost more than 200,000 yuan. BYD's E6 is even priced at 370,000 yuan. Add that to the paucity of charging stations, and the average Chinese consumer has little motivation to buy one.

Though the price of gasoline has been rising in the past years, it is still much more economical to use a traditional car than owning an electric.

Though some people in China may want to buy electric vehicles, residents in only six cities can get central government subsidies under the "Ten Cities, Thousand Vehicles" demo project. They are Changchun, Beijing, Hefei, Shanghai, Hangzhou and Shenzhen.

Of the cities, Changchun is obviously not suitable for electric vehicles at its current technology level, and its very cold environment will dramatically reduce the lithium-ion battery's performance.

By 2011, the number of drivers of all-electric vehicles in each of the demo cities had grown to only a couple of thousand under the current subsidy scheme. Therefore, it is hard to imagine that the numbers will grow enough to meet the 2015 target in three years without the introduction of new subsidies.

Tech bottleneck

Currently, China is suffering from a technological stumbling block because large batteries are currently needed to supply an electric car enough energy to drive 300 to 400 km. However, the battery will make the vehicle much heavier than a gas-powered car of the same size.

For example, a BYD E6 weighs 2.3 tons compared to the average weight of a comparable gasoline-powered car -1.6 tons. The battery weighs 700 kg, meaning that it has to expend large amounts of energy just to move its own weight.

Of course, carmakers can install a more lightweight battery into a smaller car. This way, a proper-sized battery will not make the car too heavy and can supply a reasonable driving range per charge of 120 to 180 km.

But Chinese consumers have a preference for larger cars and are not likely to pay a high premium for such a small car. The driving range limits the car's function to daily commute only, which means a family would have to own at least two cars: one conventional car for long-distance driving and a small electric. Few families in China have the means or inclination to do this at the moment.

Though a plug-in hybrid can drive longer because of its two power systems, the car usually needs to be relatively larger and is expensive too, not to mention that insufficient charging facilities exist. In many cities, the local governments have built only about 200 to 300 charging posts since 2009.

Though replacing the battery can be a solution, it will require a very high level of standardization of the battery interface. Also battery replacement stations will need to be located on prime real estate within cities, making the investment expensive. Besides, automakers do not want to lose control of the battery to a third party.

Furthermore, there are technical complications with batteries. A large electric vehicle battery pack is assembled from many cells, and there is a high requirement for each battery cell's quality and performance. If one lithium-ion battery cell does not work well, the whole battery pack will be affected or destroyed.

Not a simple matter

Large-scale battery cell production is not a simple matter. A cell is made from chemical materials, which cannot be standardized in the same manner as other technologies, like IT products. There is even a question of whether the battery industry in China has the capacity to produce 500,000 high-quality large battery packs in three years.

Many people believe domestic manufacturers can "frog-leap" over foreign automakers by promoting electric technology in China. This is based on the rationale that local manufacturers lag too far behind in the conventional vehicle sector, giving them the impetus to develop cars for a niche market.

Actually, most of the key components of electric vehicles come from multinational suppliers, and few hold an illusion that China is leading the electric car industry around the globe.

Few government planners have doubt that electrification is the ultimate route for automobiles, but there are still strong reservations about whether it is possible in three to five years. If a technology is more futuristic by nature, it might be a good idea for the government to let the technology develop on its own instead of pushing it forward artificially.

The author is the managing director of Automotive Foresight (Shanghai) Co Ltd, who can be reached at [email protected]

Related Stories

Auto China 2012 2012-04-20 11:04

Records abound with Auto China 2012 underway 2012-04-23 09:43

China 'can still lead' electric vehicle sector 2012-04-20 21:47

China sets focus on electric, hybrid cars 2012-04-19 07:23

BAIC: Range of new models set for Beijing show 2012-04-16 14:28

- Students see profit in business studies overseas

- Market to have more say in yuan value: PBOC's Yi

- Group-buying sites hit by consolidation

- China's Dongfeng plans aggressive auto export

- Wen's visit to Germany highlights strategic ties

- Listed firms see narrowing profits

- Getting the message across

- China mineral stocks running low