Society

Living for the dead

By Jin Zhu (China Daily)

Updated: 2010-03-26 07:35

|

Large Medium Small |

Morticians put final touches on deceased

Beijing - It would look like any other ordinary workplace if it weren't for that coffin lying in the middle of the room.

Vacant but for a cabinet, chair and sink, this room is where the deceased are prepared for a final send-off.

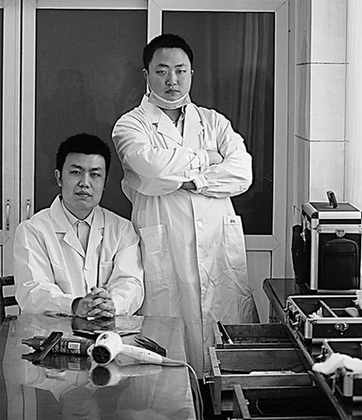

Zhang Yan (L) and Zhang Qi, morticians at Beijing's Babaoshan cemetery, are seen in their office on Wednesday. ? |

"I try to learn about who the person was when he or she was alive," said Zhang Qi, a mortician at Beijing's Babaoshan Cemetery, one of the country's best-known funeral homes.

"Even if two bodies share some features, each may require an entirely different style of makeup," he told China Daily.

"If he was a soldier, it might be better to include some red tones to create a stronger image. If she was a young girl, I will try to make her look more beautiful, as if she were still alive," he said.

In the photo provided by Beijing Funeral and Interment Administration, the two do makeup for a dead person. ? |

Qi, 25, is the youngest mortician in the office and started working there three years ago. His co-worker, Zhang Yang, 28, also arrived at the parlor three years ago.

Their jobs are not like those that many other young Chinese born in the 1980s would dream of doing.

Yet seeing dead people and their grief-stricken families helped Qi gradually realize the significance of his work.

"To satisfy the requirements of the dead peoples' families is the most important thing," he said.

That hit home for Qi in August 2008 when his grandmother died and he volunteered to prepare her body to be laid out. "I was hesitant and wondered if I could stay professional when faced with my own family. However, I believed it was the best way to be a filial grandson," he said.

Qi said he developed a deeper understanding of a mortician's role the moment he touched his grandmother's face. He has found that working with the dead has given him a different perspective on life.

The room where they prepare the bodies is wrapped in silence. Outside, the streets are noisy and bustling. "In the office we're working for dead people. When we finish we're with the living," Qi said. "It's a totally different world."

Work for the morticians begins at 7 am every day and ends at 4 pm. They begin by looking over the bodies, then bring out makeup, wax, brushes and a few color keys.

"Some people may have taken quite a beating from traffic accidents and their wounds must be sewn and patched with wax before they can be hidden with makeup. These require a mortician to be highly skilled," he said.

The funeral home depends on their expertise whenever important tasks need to be carried out.

Earlier this year, when eight Chinese peacekeepers died after a massive earthquake hit Haiti, the two young morticians were appointed to work on the bodies.

"The corpses had rotted badly, which made the work much harder. On average, we need 15 minutes to handle one corpse. But for the eight heroes, our work lasted for eight hours," Yang said.

"I was deeply saddened when we saw them. I knew my responsibility was to rescue their original faces from death to give their families at least some comfort. I tried my best to make the deceased look like he or she was sleeping," he said.

So far, Qi has dealt with hundreds of bodies. But he still encounters challenging situations.

A few days before the Beijing Olympics in 2008, Qi found himself in a dangerous situation when he applied antiseptic to the body of a foreigner.

"There was a wound on my finger and his blood got into my glove. I thought nothing of it until the embassy later told me that the body belonged to an AIDS patient," he said.

"Everyone around me was worried, but I wasn't too concerned. I took a blood test and for the three days that I was waiting for the result I kept thinking I couldn't be that unlucky," Qi said. "And everything turned out fine."

Still, the experience taught him to be more careful in his work.

For Yang, becoming a mortician started after he held a string of jobs, including work as a salesman and hotel waiter. But he found no passion for any of these positions.

"One day, I ran across an advertisement saying the Babaoshan Cemetery was recruiting. I decided to give it a try," Yang said.

"I know many people are worried about workers coming into contact with dead bodies every day. It was extremely taboo. Fortunately, my family and friends understood why I chose this," he said.

His choice is part of an upward trend for jobs in funeral homes - positions that job hunters used to shun, he said.

"Especially among most young people who have an objective understanding of death, it can be nice work that offers an average salary of 5,000 yuan ($740) a month and other competitive benefits," Yang said.

Both morticians are also planning to marry their girlfriends this year and all are totally committed to the industry and understand everything it offers.

"Morticians work to provide people with final dignity," Qi said.