Living in the Shadows

Updated: 2012-01-15 09:15

By Zhang Zixuan (China Daily)

|

|||||||||||

|

It is a shining example of grassroots folk craft kept alive for more than 2,000 years. Chinese shadow puppetry encompasses both the performance and the delicate art of making the leather puppets. Zhang Zixuan travels across China to track down the masters. Related video

The light shines out under the curtain of night, and as we approach, it gets brighter and stronger, just like the music and singing from the same source. We finally see what it is - a translucent cloth illuminated by a single bulb, a canvas for the colorful silhouettes of cut-out figures acting out the story of how the folk hero Zhu Yuanzhang rose from his peasant roots and overthrew the Mongolian Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), and then founded the Ming empire. Despite runny noses from the frigid cold, members of the audience sit cross-legged on the frozen earth in front of the stage, entranced by the performance. In Huaxian county, Shaanxi province, where it all began more than 2,000 years ago, shadow puppetry is still very much a part of most any important occasion in village life - be it birth, death or marriage. The performance in front of us, for example, commemorates a funeral. For puppeteer Wei Jinquan, the sadness is doubled. He buried his father, shadow puppet master singer Wei Zhenye only four days ago. The senior Wei was 81, and among those who had gathered to perform in his honor was his son.

Although his heart is still heavy, Wei Jinquan continues with the show.

"It was tough sending off my own father," the 47-year-old admits, even though he has performed at countless funerals throughout his career and will continue the tradition.

He's still coping with the pain, but Wei makes sure his troupe turns up at 5.30 pm sharp at Shengshan village, where the show is at that night.

|

All tasks are handled by the five-member troupe, and they will handle everything from setting up, to playing the music, prepping the props and of course, manipulating the puppets and making them come alive for the audience.

The most representative work is something called Wanwan Qiang, a singing style famous for its delicacy and exquisite tones, delivered with heart-tugging pathos.

As the white canvas goes up, stretched tight across the front of the stage, the space behind is draped in black, leaving only a narrow path for the performers to squeeze in and out.

Within 20 minutes, the stage on stilts is ready.

Dong Jinshui, 68, troupe leader and vocalist, tells the others to eat. The family courtyard is packed with village neighbors here to pay their condolences and food is being served as guests arrive in waves.

Wei and his troupe sit down and eat, passing along a cup with fiery white spirit that is refilled again and again.

"It will be a long night," they tell each other. "Drink more to keep warm and to keep up your strength."

|

The puppets, the microphone and the musical instruments are all ready, as well as a full flask of drinks in a thermos bottle. A packet of cigarettes is handed around by a member of the host family. In the next four to five hours, no one will be able to leave the enclosure, not even for a bathroom break.

Wei sits in the middle behind the backdrop and starts manipulating the puppets. A full-length play usually involves more than 60 figures so moving several puppets at once is nothing special for him.

Dong, the solo singer, will deliver all the songs in the play. When the act features crowds or armies, his fellow troupers will join in the chorus. Apart from singing, Dong also plays the yueqin, a two-stringed instrument as well as the drums and gongs.

Another musician is Liu Xingwen, who plays banhu, another string instrument, and suona, the little Chinese trumpet. More importantly, he is in charge of making sure the right puppets are ready for Wei when he needs them.

Eager to see the play, the villagers have all finished dinner early and are gathering in front of the stage to make sure they get the best view.

Wu Hongxin, who is from the neighboring village of Wujiapu, came early with his special chair to get a good spot. He is not particularly close to the deceased but he knows the shadow-play plots like the back of his hands.

"I can recognize the play as soon as the opening notes start," the 84-year-old says with pride. He has been following these plays since he was in training pants.

Just as the fans are of certain vintage, those who practice the art are also getting old.

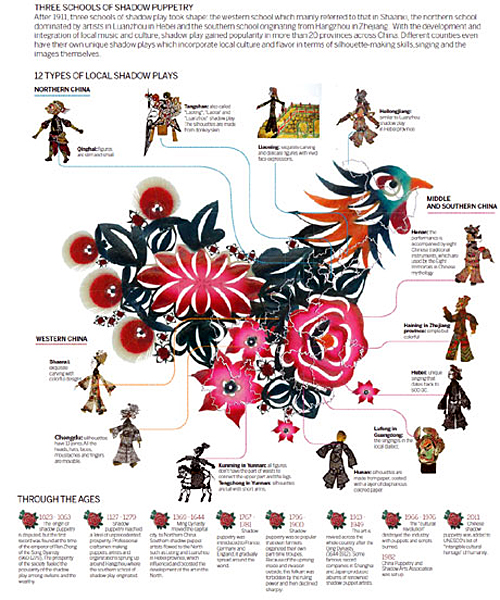

In the days when shadow puppet shows were most popular, more than 10 troupes competed with each other for elbow space at temple fairs. Now, less than 20 performers are left, and the number is shrinking as the days pass.

Pan Jingle, 83, acknowledged as the "living fossil" of Huaxian shadow puppetry, is arguably the oldest singing master still alive. He was the one who dubbed the shadow play scenes in Zhang Yimou's award-winning film, To Live.

Out of a repertoire of 200 full-length shadow plays, Pan sings Wanwan Qiang with the most vitality. His rich, high-pitched voice singing the female roles has drawn many in the audiences backstage to marvel for themselves.

But Pan is getting lonelier and more isolated as more and more of his fellow performers die of old age. He, too, cannot be as active as he used to be and his faculties are fading with age.

"It's a shame there was not more systematic documentation of all the plays while Pan could still remember them," says Wei Liqun, who was responsible for drafting the nomination of the Chinese Shadow Puppets to UNESCO's Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

When the plays are passed down via word of mouth, things get lost in transition, and less and less are taught to new apprentices. Some of Pan's best pupils are already in their 60s.

Wei Jinquan and his four colleagues are the last surviving performers, and they started as teenagers.

Dressed in their handmade wadded cotton jackets, the five country folks have taken Huaxian shadow puppet shows to as far as Germany, the United Kingdom and France, and received overwhelming praise for their art.

That's why no one could be happier when Chinese Shadow Puppetry was officially inscribed on the UNESCO's Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in November 2011.

But after the exuberance comes the worry. What if no one inherits the art form?

"Many young people are learning but none are willing to work as performers."

Wei explains that an all-night performance only brings in about 1,000 yuan ($159) for the whole troupe.

"The traditional plays are also losing audiences," Wei says. "Perhaps producing newer plays with multimedia presentation may be a workable solution."

But while they can, Wei's troupe will still continue performing on their rural stage.

"That's where Huaxian shadow puppetry has its roots."

Contact the writer at [email protected]. Lu Hongyan also contributed to the story.

|

Related Stories

Shadow puppetry enters intangible heritage list 2011-11-27 19:49

Hot Topics

Kim Jong-il, Mengniu, train crash probe, Vaclav Havel, New Year, coast guard death, Internet security, Mekong River, Strait of Hormuz, economic work conference

Editor's Picks

|

|

|

|

|

|