Technology helps save arable land, increase food safety and yields

Countries in East Asia, including China, with limited resources, are looking at "plant factories" - a kind of artificial farm that doesn’t use arable land - as a way to provide adequate food supplies for rising populations.

Yang Qichang, a leading agricultural technology scientist at the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, said plant technology that doesn’t need soil is expected to help countries like China, Japan, and South Korea achieve their ambitious targets of food self-sufficiency in the coming decades.

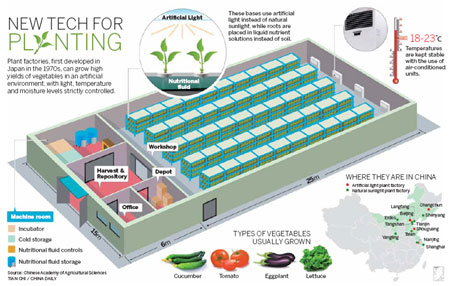

Plant factories, which originated in Japan in the 1970s, are considered a successful way to get high yields via control of growing conditions, such as light, temperature and moisture, in a closed space.

|

|

Yang Qichang, a leading agricultural technology scientist at the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, checks vegetables growing in a plant factory in Beijing. [Photo by Feng Yongbin / China Daily] |

Yang, director of the Center for Protected Agriculture and Environmental Engineering at the CAAS, said the advantages of plant factories include their limited demands on the environment and limited need for quality land. Those traits help countries that face shrinking arable land and frequent natural disasters.

In a 10,000-square-meter plant factory in the CAAS, vegetables such as lettuce, tomatoes, eggplants and cucumbers - common in a Chinese diet - have been planted in a special nutrient solution.

Because they are not grown in soil, the vegetables are beautiful and clean.

"Because there is almost no need for agrochemicals, such as pesticides and fertilizers, the vegetables are attractive to people who are concerned about food safety," Yang said.

He said growing vegetables in plant factories is a physical process, and the seeds are the same as those sowed in the field, so there is no need to worry about food safety.

Yang said vegetables from plant factories now follow the same food safety standards as plants from the field, but generally speaking, they are of higher quality because they contain fewer nitrates and more vitamins.

"In China, scientists have gone about as far as they can go with conventional ways on agricultural production," he said.

For instance, wheat yield is 4.61 metric tons per hectare compared to the world average of 2.76 tons. Per-hectare rice and corn yields are 6.38 tons and 5.28 tons, compared to the global average of 3.38 tons and 3.41 tons, according to the CAAS statistics.

"The room for increasing production seems limited, but not for plants in plant factories," he said.

Such an advantage would certainly help China.

|

Agriculture experts warn that China may have a difficult time feeding its growing population - expected to peak at about 1.5 billion by 2030 - if natural disasters increase in frequency.

From 2003 to 2009, the total grain loss from various natural disasters was 303.35 million tons - more than four times the increase in output over the same period, CAAS statistics showed.

"Nearly 60 percent of the grain loss is caused by drought. The other main causes of crop loss are floods, plant diseases and insects," said Li Maosong, a researcher on disaster reduction at the CAAS.

"Therefore, for China, reducing agricultural loss caused by natural disasters is as important as increasing output. Plant factories, keeping out most natural disasters that hit the country, will surely show its importance in the future.

"It can be built everywhere we want, even in deserts and on islands," he said.

By 2011, more than 20 plant factories spread over 10 provinces and municipalities in China have included 20 varieties of vegetables, CAAS statistics showed.

The varieties in plant factories in China still lag behind those in Japan, which has nearly 60 varieties, including not just vegetables, but vegetative medicinal materials as well, said Tong Yuxin, a CAAS researcher.

Japan accelerated its construction of plant factories after a devastating earthquake and tsunami last year created nuclear pollution, Tong said.

"Building more plant factories is a good choice for Japan in its stricken areas, where it is not safe to plant crops on land because of nuclear pollution," she said.

|

|

Yang Qichang, a leading agricultural technology scientist at the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, checks vegetables growing in a plant factory in Beijing. [Photo by Feng Yongbin / China Daily] |

According to Yang, with a total investment of 150 billion yen ($1.9 billion), Japan is expected to triple the number of plant factories to 150 within the next two to three years.

Vegetables from plant factories do have one disadvantage, at least for now.

Agriculture professionals said that because of the high cost of production, the price of vegetables grown in plant factories is several times higher than that of common vegetables.

For instance, a head of lettuce grown in a plant factory with artificial light now sells for about 15 yuan ($2.40), about five times more than an ordinary one.

"I just buy and try. I cannot afford this over a long time," said a local resident in Shuangan Department Store in Beijing.

Yang agreed. "What we need to do now is try to lower the cost of planting vegetables in plant factories, so that such products can go on the market in large quantities to benefit more people," he said.

Yang urged authorities to offer subsidies to enterprises that want to build plant factories.

"Apparently, the importance of such advanced technology to ensure food safety in China has not been realized among many officials," he said.