In 1995, right around the time Fortune magazine published its cover story The Death of Hong Kong, and declared the old colony's heyday over, Sandy's family got the news they had been awaiting for 10 years - their emigration had been approved.

Sandy, who did not want to reveal her full name, was 17 at the time and in her final year at high school. She was grateful to her parents when they put off the family's relocation to the United States long enough for her to celebrate one last birthday in Hong Kong with her friends. Within months, though, the family had made its break and was in New York.

"Many people were talking about emigrating before the return in 1997," Sandy's father recalls. "They were a little bit panicked, I would say."

Back then, after the Sino-British Joint Declaration of 1984 had made it clear that Hong Kong residents would not all be able to relocate to the UK, many worried about the uncertainty surrounding the historic transition of authority and started to look for other countries that would take them. Most headed for Canada, Australia and the US.

The emigrants, mostly well-educated urban people from the middle or upper classes, were concerned about their careers and lifestyle prospects in Hong Kong. Most hoped to find a better life elsewhere. The leading reason most gave for their unease was the political transition for the city after the return.

Academic studies show that migration from Hong Kong soared from 22,400 in 1980 to a high of 66,000 in 1992. In total, around 600,000 people left between 1984 and 1997, according to government statistics.

Nan Sussman, associate professor at City University in New York, says the number could be even higher and might have hit 800,000.

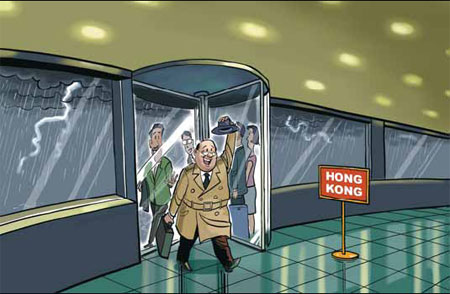

But the tide has turned in recent years and, since 2000, the number leaving each year has slowed to a trickle.

Sandy's family was typical of many that left. Her mother filled out her immigration application in 1985, hoping to be near her sister, who was already a US citizen.

For Sandy's father, who was in his 40s, the prospect of moving away from all that was familiar was frightening.

"It was like starting over from zero," he says. "I was worried about everything - getting water and electricity connections, making new friends, everything. And what if I could not find a job?"

But the potential pitfalls were offset by potential advantages.

"It was going to be good for our daughter," he says. "She would be able to go to a university in the US as a US citizen."

Sandy remembers that there was little for her to worry about at the time - neither the upcoming political transition nor the possible move to the US.

"I was not worried. I mean, yes there was a question mark, but I was not afraid of it," she says. "I think it was a matter of confidence. The city had been peaceful for 99 years. People worried that the city would become like the China of the 1950s and 1960s ... I guess that's why they were worried but I had no such experiences."

In the US, Sandy got to go to university, just as her father hoped, and studied social work as she had always wanted. Her English improved very quickly. She enjoyed Western food. But there was something missing.

"I was a young girl, I liked shopping, buying something cute, but the clothes there were not right for me, too Western. Even the cartoon characters were not the ones I was used to seeing. There was no Hello Kitty."

Sandy had deep feelings for Hong Kong and missed her old life.

"We didn't have the Internet before in Hong Kong like we have now and life was simple before we left," she recalls. "Meeting friends was really meeting each other and hanging out at the Peak, Repulse Bay, Tsim Sha Tsui. People were hardworking. Entertainment, like movies and songs, was really good quality. Hong Kong people were more independent and diligent at that time, they didn't rely on the government for everything like nowadays."

So, with her heart pulling her back, she returned to Hong Kong after graduation in 2000. In 2005, her parents retired and followed her. "I feel at home here," she says.

Her father, too, is glad to be home. "I feel as if nothing has really changed here, just the chief executive," he says. "Everything is easier for us here. Even buying stuff is more convenient."

The family, so typical of those that left Hong Kong in the 1990s is now representative of the huge number - academics believe about half - that returned.

The book Hong Kong Movers and Stayers, which was published last year, notes that there are idiosyncratic cultural explanations for the flood of people who left Hong Kong in the 1990s and for the great wave of returnees. It says Hong Kong people, who lived under British rule, in a "borrowed place" on "borrowed time", were prone to migrating.

Clement So York-kee, a professor at the School of Journalism and Communication in the Chinese University of Hong Kong, has studied news reports to understand the social trends of people returning to Hong Kong. The former school head knows about the issue first-hand; he is a returnee himself.

In 1991, the 30-something quit his job as an instructor at the university to move to Canada.

"I could feel the whole society was anxious at the time," he says. "People had doubts about socialism. They were worried about democracy and freedom. I wouldn't say it was chaotic, but people were quite disturbed.

"Most of my colleagues were making plans to emigrate. You would have been very odd not to. Even working-class people wanted to move but they did not have the means."

He says the Chinese University offered him very good terms to try to keep him.

"Big institutions, even universities, were worried about a brain drain at that time," he says. "The emigration changed the demographic structure. There was a rare talent gap at the middle-high level in many companies and institutions."

So didn't plan to stay in Canada forever and, after a few years, he returned to Hong Kong and to Chinese University.

"For one thing, my parents were still in Hong Kong," he says. "Also, with my academic background, Hong Kong was a place where I could do something."

He estimates that two-thirds of migrants in similar circumstances have returned.

While middle-class people fled Hong Kong before the return largely because of concerns about the political future of Hong Kong, So says that the city did not suffer from the "handover hangover" many feared. Politics seems to have faded into the background, while Hong Kong's economic opportunities and cultural life have grown.

Migrants have also come to realize that Canada, the US and Australia are not the Western Shangri-Las many migrants hoped for.

"They can easily point to disadvantages such as high taxes, cold weather and cultural differences," So wrote in his research paper.

"Some persevered in order to get passports before hurrying to leave their adoptive countries. In contrast, the Chinese mainland has become a new land of gold for Hong Kong natives, returnees and foreign opportunists."

Ironically, the exodus and return of so many people may have been good for Hong Kong because it has strengthened the diversity and overseas links of the special administrative region.

A survey by the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada in 2010 showed that conservative estimates put the number of Canadian citizens living in Hong Kong at 295,930. Some 83 percent of them hold both Chinese and Canadian citizenship and two-thirds have immediate or extended family still living in Canada. The Australian consulate-general in Hong Kong believes as many as three-quarters of Australians living in Hong Kong also hold dual nationality.

"Hong Kong is my first home, Canada is my second," says So. "I'd describe myself as a Hong Kong Chinese with some North American influence, not simply a Hong Kong resident."

Among the returned migrants, many who were youths when they left and who grew up abroad are now making their mark on the SAR.

"For example, at lunch time in the crowded restaurants in Central, everybody is talking in fluent English and I can recognize some Canadian accents but when I turn around, they are Chinese," says Wendy, a 29-year-old who emigrated to Canada when she was 7 and returned four years ago.

Wendy, who works as a pilot, returned to Hong Kong after her graduation seeking better career opportunities. She now works for an international airline. "I plan to stay in Hong Kong for the foreseeable future," she says. "Hong Kong is a great place to live."