|

|

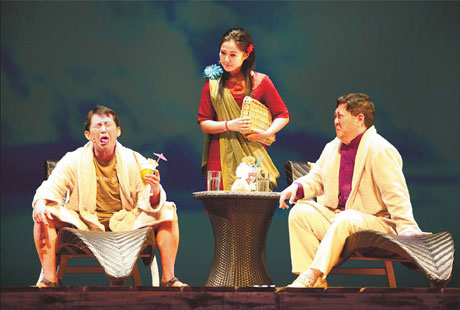

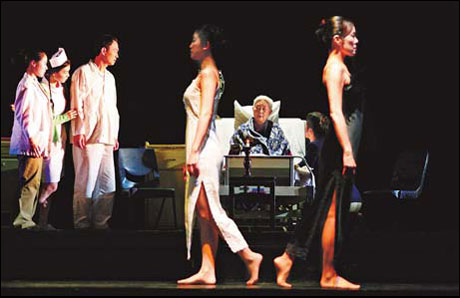

Scenes from two of playwright Stan Lai's shows, Crosstalk Travelers (above) and A Dream Like a Dream (below). Photos Provided to China Daily |

Stan Lai and his Taiwan-based Performance Workshop have been sweeping the mainland with their fresh approach.

Lu Ren experiences wild mood swings as his application for a US visa is rejected and then accepted.

He first kowtows to American visa officers, then launches a diatribe against what he perceives as American evils, then eulogizes the US as he gauges the situation, often incorrectly.

Lu Ren, whose name is a homonym for "traveler", is one of three characters in a new stage production currently touring mainland China.

The above scene is the highlight of the play that keeps audiences laughing almost non-stop. Lu's love-hate relationship with a US visa, or the US in general, strikes a chord with many middle-class members of our society.

Crosstalk Travelers is the latest of a dozen shows Taiwan-based Performance Workshop, commanded by Stan Lai, has taken to the Chinese mainland since the tour of Red Sky in 1998, and its materials were derived from Lai's personal experiences.

Lai, 56, is a titan of Chinese theater. Many consider him the greatest Chinese playwright of our generation, ranking with Cao Yu and Lao She who were in their prime in the first half of the 20th century. His influence in the Chinese-speaking world is such that his productions have become a byword for quality, winning kudos from critics and the ticket-buying public alike.

But Lai did not start off aiming high. He tinkered with a traditional form of grassroots entertainment known as xiangsheng. Usually translated as "crosstalk", it originated in Beijing and spread to Taiwan when the Kuomintang army retreated to the island in 1949.

Xiangsheng is the equivalent of stand-up comedy in the US except that it usually has two performers, one setting up the situation and the other delivering the punchlines. Lai has researched the parallels between the Chinese and American genres.

"During the time of vaudeville," he says, "stand-up comedy also had two performers, like Abbott and Costello." He has translated many of the duo's baseball routines into Chinese because the sport is popular in Taiwan.

Nowadays, American comedians, such as late-night television show hosts, all go solo and deliver monologues that make fun of the day's news. They resort to one-liners. That, in Lai's opinion, reflects the fast pace of American society.

In traditional xiangsheng, a punchline would take four or five steps of mild bantering to reach.

Xiangsheng was on its deathbed in Taiwan when Lai presented That Evening, We Performed Xiangsheng, in 1985 - as an elegy for the genre. It inadvertently revived it, creating a new form of stage entertainment called "xiangsheng play". It also set a record for the number of stage performances and audio-cassette sales.

Since then, there have been seven xiangsheng plays from Lai's Performance Workshop, including the latest about worldwide travels. A genre that originated in teahouses and consisted of standard stand-up routines has been elevated to a theatrical art.

Xiangsheng is free-flowing, going from one topic to another. Yet, Lai's plays have an inner cohesion so strong they boast not only focused themes but intricate structures. The two acts of Millennium Teahouse (2000), for example, are set 100 years apart. The parallels are striking. In one segment, the simultaneous narrations of two actors are seamlessly woven into a whole, creating a dramatic effect that is tantamount to a movie montage.

You'll not be surprised to learn how solidly trained Stan Lai is in the art of theater. At a recent week-long Beijing forum, the PhD in dramatic art from the University of California at Berkeley (1983), and professor and founding dean of the College of Theater at Taipei National University of the Arts, gave a rundown of theatrical masters - from Aristotle, to Shakespeare to Chekhov. Instead of getting deep into theories, he emphasized the basics. For all his achievements, he is not someone who flaunts his craft, but lets it serve the story he wants to tell.

Or, two stories, as in the case of Secret Love in Peach Blossom Land (1986), a play that has attained mythical status with its frequent tours and endless permutations, not to speak of an award-winning film version.

Two performing troupes are each rehearsing a play, one about a pair of lovers separated during China's civil war in the late 1940s, and the other about a rural trio whose entanglements drive the husband into self-imposed exile and a dreamland that exists only in ancient literature.

The weepy melodrama and low comedy join in one scene to produce a hilarious exchange that appears to be spontaneous but does not miss a beat in timing.

The work he cherishes most, judging from how frequently he mentions it, is A Dream Like a Dream (2000). It defies most theatrical conventions, being eight hours long and having the performers surrounding the audience. The multi-thread plot can be summed up as such: "In the story someone has a dream; and in the dream someone tells a story."

In the Beijing lectures, Lai detailed the inspirations for each of his plots - the dying patient who reveals his past to a novice doctor, the portrait of a Chinese woman in a French chateau, the marriage of a French diplomat to a Shanghai woman, the mysterious disappearance of a man after a train wreck, and so on. It has been staged in Taiwan and Hong Kong, and Lai dreams of presenting the complete version in Beijing.

Lai's theatrical works have a reputation of speaking to diverse segments of the audience, high-brow and low-brow alike. Despite the occasional forays into experimental productions such as Dream, much of his oeuvre displays a feel for everyday life. "It is good to be close to reality," he says, "but if you are too close, you risk getting outdated."

He is also willing to adapt his works for mainland audiences. Most of the foreign terms in Crosstalk Travelers are given mainland translations when they differ from Taiwan's. He says he also takes out content too specific to Taiwan politics.

When a selection of Millennium Teahouse was chosen for CCTV's Spring Festival Eve gala, arguably the highest-rated show in the whole world, he had to revise it so it accorded with the stringent rules of the censors.

And Lai survived that experience so well that he later took on a project commissioned by CCTV. The result was Light Years (2008), a play that refracts three decades of Chinese transformation through the fate of a small black-and-white television set. It was supposed to have an extended run at the newly built CCTV building, which was sadly burned down shortly before it opened.

But sporadic tour shows and a stellar cast have turned it into a hot ticket. In an earlier review, I commented that, "It has the CCTV logo, but manages to avoid all CCTV pitfalls".

On an even larger scale was The Village, produced in the same year but encompassing 60 years of turbulence. This time, the location stays the same - an army village in Taiwan province where retreating Kuomintang soldiers and their families settle down. This is a story few mainlanders are familiar with, and it is about the enemy of the Communist winners, yet the mainland audience virtually breathed with the characters on stage.

The tears and laughs, sometimes alternating and occasionally simultaneous, kept pouring from the audience. Judging from the reception alone, The Village can be ranked as a towering achievement of Chinese performing arts.

Artistic dexterity aside, the play has the subtle function of bringing together political factions - mainlanders and Taiwanese, and inside Taiwan, the blue and green camps. Two of the most emotional scenes in the story subtly comment on mainland-Taiwanese relations. In the first, an old lady from an army family dies and a destitute family member goes to buy a coffin. He cannot afford a regular one. So, he asks two Taiwan carpenters to make one, for a ridiculously low price. Contrary to their common business sense, they accept.

In another place, the Taiwan wife of a Shandong soldier pays his ancestral home a visit after a 30-year absence and finds he had a wife before fleeing the mainland. The audience does not realize the truth until he asks her to call the woman "big sister". Instead of throwing a jealous tantrum, she gathers herself and showers the woman and her children with gifts.

In both cases, the generosity of the Taiwanese comes through and touches many hearts. These are perhaps two of the greatest scenes in Chinese theatrical history. After watching them, one may think less of the politics that divides us and more of the humanity that binds us. Lai's work never preaches, but it has a conviction that transcends petty conflicts.

One would think artistic vision like this comes from a single strong source. Actually, it is the result of collective efforts. Lai's method is deeply rooted in improvisation. His work process consists of setting up a framework and having his actors invent their own lines as they rehearse. He then decides what to keep and what to leave out. The group dynamics often yields the best dialogues and plots one can imagine.

When recounting the magical moment of the lovers' reunion in Secret Love in Peach Blossom Land, Lai himself marvels at how the actors - his wife Ding Nai-chu played the female lead - got it right the very first time. "As she was leaving the hospital ward, I was silently pleading, 'Stop her! Ask her back!' Then he (the male lead) suddenly asks 'Did you ever think of me in those long years?' Which opened the floodgate of emotions."

Lai's eminence as a playwright and director can be attributed to many factors, but what stands out as unconventional in the Chinese-speaking world is his ability to elicit not just the best performances from his actors but the best lines. To borrow a phrase from music, of which he is a connoisseur and whose structures influence his theatrical output, he is at the same time a composer and a conductor. Or, he uses conducting to compose.

When asked whether he represents another golden age of Chinese theater, he says, with characteristic modesty, that he hopes Chinese stage plays will reach new heights of artistic splendor: "If I may be of some help to someone producing a great work, I'll be very happy."