|

|

In May and June, the Honghe Hani Rice Terraces are a patchwork of fresh green. Li Jincan / for China Daily |

|

|

Father and son return from the paddy fields, with a fish for the dinner table. Photos by Li Jincan / for China Daily |

|

|

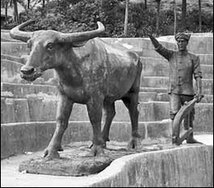

In the public square of Yuanyang Old Town, a set of bronzes commemorate the farmer and his water buffalo. |

Related: Honghe rice terraces micro - ecology

This is an isolated paradise where man and nature have lived happily together for generations. But besides being a favorite perch for photographers all over the world, the Honghe Hani Rice Terraces deserve recognition for more than just scenery for pretty pictures. The China Daily Sunday team of Wang Hao, Pauline D. Loh and Cang Lide takes to the hills and roots out the reasons why.

Every Hani has a song in his heart. It is these songs that have channeled the wisdom of their ancestors down through the ages. And now, while the rest of China spirals towards urbanization at breakneck speed, it is these songs that keep the Hani in harmony with nature and with themselves - almost like musical mantras for protection.

The Honghe Hani and Yi autonomous prefecture lies deep at the bottom of Yunnan province, in Southwest China. Go south past the prefecture and you hit the China-Vietnam border soon after.

It is this relative isolation that has preserved the Hani Rice Terraces and its dual heritage of an ethnic lifestyle intimately connected to the land, and the secrets of keeping an ecological balance that results in rice fields perennially rich and lush while the rest of the region thirsts in a three-year drought that is only just starting to break.

It takes a lot of rain to slake earth parched and cracked for so many growing seasons.

But, on the Honghe Hani Terraces, the land has been kept moist and fertile, and the only cracks that are appearing here seem to be threats on the horizon.

Local authorities and concerned community elders are grappling with the problems of a restless younger generation eager to try out the attractions of the big city.

These temporary temptations can do permanent damage to the Hani heritage if another type of balance is not brought about soon.

How do you tread the tightrope of giving the Hani all the advantages of 21st century life while helping them preserve a precious, proven self-sufficiency?

To solve at least some of these headaches, the Hani Rice Terraces Association was set up in 2003.

It is headed by Zhang Hongzhen, also the director of the Honghe Hani Rice Terraces agriculture board, a dynamic advocate of Hani culture who has gathered a dedicated team about her.

She personally led us on a two-day tour of the terraces, allowing us access to community leaders and villages that the casual tourist will never get.

One of the association's recent achievements had been to get the rice terraces listed, in June 2010, under the Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems Pilot Sites (GIAHS) of UNFAO, the United Nation's Food and Agriculture Organization.

The current buzz for the Rice Terraces is an application to get recognized as an UNESCO World Heritage Site as a cultural landscape.

Zhang, 48, is a Hani from the Red River and she quotes from the songs often. In fact, she had them documented and published in Chinese from the original Hani language, and then translated into English. The volume is called the Songs of the Four Seasons.

This little book is part of a bigger series that Zhang and her team painstakingly researched, edited and published.

It is an encyclopedic collection that covers every aspect of Hani culture and lifestyle, with particular emphasis on the macro and micro ecosystems that make the region so unique.

As Zhang showed us around her beloved rice terraces, she recites a Hani song as she climbs with us:

"While all the stars are partying in the sky,

The palm trees are dancing happily on the earth."

The images conjured by the easy ditty can still be seen everywhere at the Honghe Hani Rice Terraces.

It is a well-preserved, sustainable eco-agricultural system and a unique agro-ecological cultural phenomenon borne out of the ancient wisdom of the Hani - a carefully choreographed harmony between man and nature.

In yet another song of the four seasons, the Hani are reminded, "the wisdom of past sages is like oil squeezed out of rock, and it is the life blood of our people."

There is a lot to be proud of. The forested hilltops, the village hamlets with their mushroom thatched roofs, the terraced rice fields, the little reservoirs and wetland patches, the underground water and the water network above ground - these are the visible aspects.

The intangible part of the heritage include the rich ethnic diversity of the Hani and Yi people, their oral history carefully preserved in songs and stories, the folk rituals and customs and most of all, a sustainable lifestyle that flows along with the natural energies of nature.

It is a combination of nature blessing the land, and the people appreciating and protecting these benevolent gifts.

That is the reason why the terraces have consistently good harvests, independent of the whims of drought or flood.

In this seemingly paradise-like existence, seeds of discontent have been sowed by the challenges of encroaching urbanization.

As we wandered among the rice terraces, some patches of fields were lying fallow, the surface cracked with neglect. It is not that these particular segments are any less fertile, it is because there is no one to tend them.

The families they belong to cannot afford to employ farm workers, and the young are away in the big cities.

Those left behind, the elderly, no longer have the strength to work their paddy fields.

Part of the problem, like many similar lowland agricultural enclaves, is the poor prices the grains command in the open market.

While the micro-ecology of the rice terraces can comfortably feed a family, there is little or no money for other modern day necessities like the electricity bill, televisions, computers, the post-'80 and post-'90 must-have gadgets of smartphones and tablets.

The rice varieties planted here are heirloom species, and do not yield the huge harvests of cross-bred rice plants.

Another reason cross-bred rice does not do well here is the need for pesticides and chemical fertilizers, which the Hani wisely resist.

Their terraces are fertilized by organic waste of buffalo, pigs, chicken and ducks, as well as green compost from fallen leaves and rotting weeds.

Their plants are kept pest-free by foraging chickens and ducks.

They are also fiercely protective of the red rice varieties grown here and would eat nothing else.

The red rice is descended from wild species cultivated for more than a thousand years since the first Hani settlers came to the Honghe region.

By now, it has evolved to include more than 20 sub-species including white, red, purple, glutinous and non-glutinous varieties.

To keep the gene pool healthy and disease-resistant, the Hani regularly exchange seed rice with neighbors from another village or another side of the mountain.

Right now, the whole question of conservation hangs on the balance.

Living standards are comparatively low, and fall way below the national average.

To catch up, the Hani must push their products beyond their homes. They also need to welcome more visitors with spending power.

Tourism is a double-edged sword that must cleave a balanced path between profit and preservation.

While it can and should be encouraged, too many feet trampling about the rice terraces may also destroy what the visitors came to see. It has to be wisely managed.

And most of all, it is the Hani people and their way of life that must enjoy the benefits of tourism. Not the profiteers nor opportunists, whether they be private or corporate entities.

At the Honghe Hani Rice Terraces, that old adage about taking away only memories, and leaving footprints is not just a simple saying. It must be the rule of the game. Oh, and we must not forget the photographs.

Contact the writers at [email protected] and [email protected]. Li Yingqing contributed to the story.