When amateur actors have more passion and authenticity than their professional counterparts you have to question the validity of China's management of the performing arts.

On the sixth day of the Chinese New Year, I was invited to a reading of the Broadway musical Rent. What a strange time for a rehearsal, I thought. The streets in Beijing were almost empty and the buses that ran had few passengers.

The reading took place in one of the nine small theaters of Beijing's Chaoyang Culture Center. The first thing that struck me was the high quality of the Chinese translation. It was so idiomatic the parallels with China's starving and aspiring artists were inescapable.

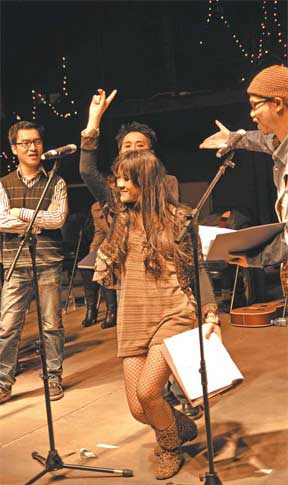

The performance oozed with raw energy. The uniformly young actors threw themselves into their roles. Sure, the chorus numbers were obviously under-rehearsed and there were a few minor roles that were miscast, with college students impersonating - not very convincingly - heroin-addicted hippies. But overall, I was really surprised by the passion and professionalism displayed.

My biggest surprise came at the end when I learned they were not students or graduates of the Central Drama Academy, but a ragtag team of musical lovers. They did not have the money to rent the theater for a complete day, just two blocks of time. The previous afternoon they were almost kicked out by the landlord before they could finish their only on-site run-through.

So, who are these people?

They are China's aficionados of musical theater, white-collar workers and college students whose knowledge of a worldwide repertory has made them die-hard fans and experts. Their platform is a website called Chinamusical.net, which was set up in 2005. It has 31,842 registered members, but as Jia Yi, one of the two producer-directors of Rent, points out, the core base is just a few hundred.

From talking to some of them, I got the impression that the watershed event in musical theater in China was Les Miserables and Phantom of the Opera, in Shanghai, nearly 10 years ago. Xu Feili watched Phantom three times, with her mother, a music teacher. This time she was cast in the role of Joanne, in Rent.

"I started taking singing lessons after I developed an interest in musicals. They gave more power to my singing voice," Xu explains.

About half of the Rent cast is from Shanghai. They have a couple of gatherings every year, putting on segments of favorite shows.

"Each of us has devoted ourselves to the study of one or two shows, and mine is Miss Saigon and Thoroughly Modern Millie," Xu says.

Xu's day job is sales manager of a hotel. The other actress, who plays her lesbian lover Maureen, works at an insurance company. Roger the rock musician is a public servant in real life. Angel, the cross-dressing boy with a heart of gold, is a pharmacist. Only the actors playing Mark and Collins have formal training in music or performing arts. The supporting roles that form the chorus hail mostly from Tsinghua University, China's MIT.

What brought them together is a shared love for musical theater and the shared platform of the Internet. They have sub-groups that devote themselves to the musical repertoires of specific countries. They post their lyric translations, singing samples and original scripts for feedback. Their translation is of such a high level that it often stands out when used as projected titles in the China tours of Western companies such as Mamma Mia.

They may be connoisseurs, but they are amateurs, and few would believe they could deliver a performance that rivals, let alone surpasses, professionals.

In China, writers and artists have circles. You have to be an insider to get recognition, or a government subsidy. But it's often the outsiders who have out-of-the-box thinking and achieve major breakthroughs. Some who show enough respect may be enlisted once they have street credibility, such as Li Yugang, who sings both male and female voices to perfection; others, like Han Han, remain defiant and reject the rebel-and-join route.

When it comes to performing arts, we have a tradition of top-down creativity. Government agencies set an agenda and artists write plays and operas in that image. These lavish productions do not attract paying audiences, so one or two token shows are given - all subsidized by the government and recorded as a feat of cultural innovation. Then the props and costumes are warehoused and may never see the light of day again.

On the other hand, there are hundreds of wandering troupes that sleep in makeshift tents and perform at farmers' weddings and funerals. They may have never heard of Stanislavski, but they bring cheers and tears from real audiences who pay to watch them. For a long time, these performers were either banned or harassed. The good thing is, the government has finally come to recognize their value and allows them to carry on.

The Rent performers are certainly not this type. They are highly educated and, though not quite polished, exhibit a high level of professionalism that is a throwback to the old-time "piaoyou". This was the loyal fan base of Peking Opera that not only set the tone for critical evaluation, but organized decent performances of their own. In a sense, they are the backbone of this performing art.

I am a big fan of Broadway musicals. I stood in line for hours to catch one of the earliest shows of Rent, on Broadway, back in 1996. I've also watched a few productions by the Central Drama Academy, including the atrociously translated Fame. I feel I have a right to be thrilled when I see a diamond in the rough.

Fortunately, the Rent troupe caught the attention of Don Frantz, who is the representative of a big Broadway production company in China. He not only provided some financial support, but sent out messages to his friends - the impresarios and critics of the city. He also provided his living room as the troupe's rehearsal space.

"The Broadway Rent started as a workshop production, something similar to this," he says, and it ended up having a 12-year run. Of course, this Rent is not eyeing that kind of lofty goal, but it may have some potential as a commercial production.

There are reportedly 250,000 people living in Beijing's basements and suburbs who are struggling to succeed just like the characters in Rent. The story, with its rock style, should speak to them. Rent was inspired by Puccini's La Boheme, about a similar bunch in fin-de-siecle characters in Paris. The beauty of this basement production is its ubiquitous local references. It could only have been done by someone who has absorbed the essence of the original, as well as understood the target market - not someone hidden in an ivory tower.

You may wonder why the Broadway Rent could run for 5,124 performances while a Chinese hit like Teahouse has yet to reach its 600th performance, and that's counting the total since its debut in 1958. There are many factors at play here, economic, cultural, political. But one difference is crucial: Broadway has a group of devout fans who, like Jia Yi, Xu Feili and their comrades, love this art form, and nurture it till it reaches a mass audience. In today's China, it may be technology-enabled advocates like them who are sowing the seeds for the future growth of this emerging art.

相關(guān)閱讀:

An elderly woman with two large pots

(作者周黎明 中國(guó)日?qǐng)?bào)網(wǎng)英語(yǔ)點(diǎn)津 編輯陳丹妮)